We independently review everything we recommend. When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Learn more›

Sharpening your own knives may seem intimidating, but it’s a cost-effective way to take what could be trash (your dull knives) and turn it into treasure (a brand new set!). Ceramic Roller

Manual and electric knife sharpeners are easier to use than sharpening stones, and the best ones are quick and versatile.

After testing 11 sharpeners—and slicing through 10 pounds of tomatoes—we think the Chef’sChoice Trizor XV is the best for home cooks. It gently puts a razor edge on dulled knives of almost every sort: Japanese- and German-style, stamped and forged, cheap and expensive.

The Chef’sChoice Trizor XV is reliable, fast, and easy to use, and it puts a razor edge on almost any kind of knife.

The diminutive Work Sharp Culinary E2 outperformed every other sharpener in its price range. It’s great for the occasional cook.

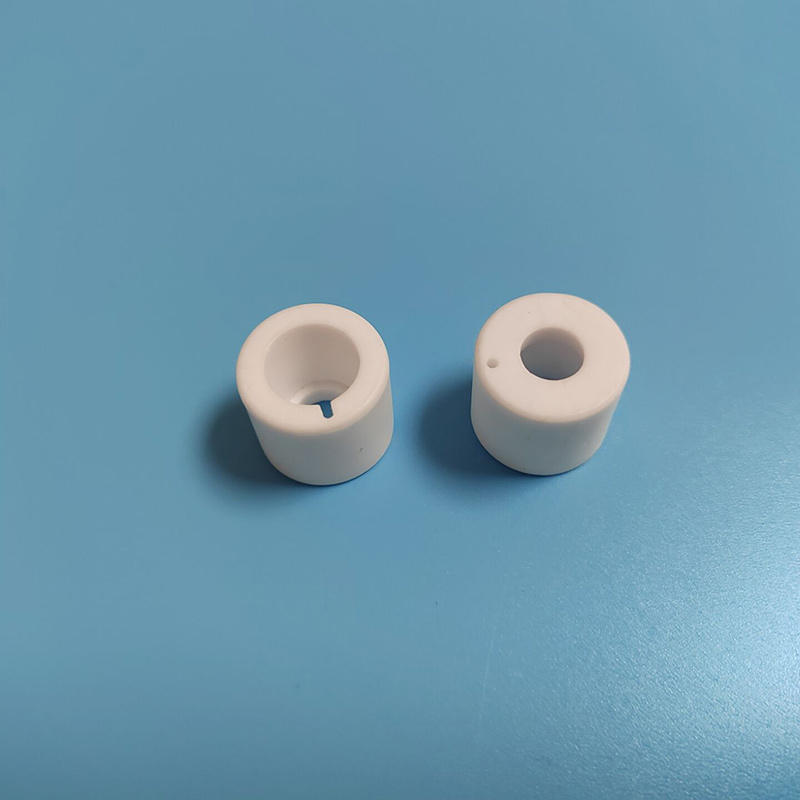

The Idahone Fine Ceramic Sharpening Rod works on any kind of knife (except a serrated one), and it’s gentler on blades than traditional steel honing rods.

The Chef’sChoice Trizor XV is reliable, fast, and easy to use, and it puts a razor edge on almost any kind of knife.

The Chef’sChoice Trizor XV produced the keenest, most consistent edges of any sharpener we tested. It repeatedly brought both an inexpensive, German-style chef’s knife and a high-end Japanese-style knife back from butter-knife dullness to one-stroke tomato-slicing sharpness. With the Trizor XV’s detailed user manual and clever design, it’s virtually impossible to mess up the sharpening process—something not every competitor can claim. And since this sharpener is both fast and simple to use, it’s easy to keep your knives sharp at all times. Finally, the Trizor XV is built to last, with a strong motor and sturdy construction. (We’ve used one in the Wirecutter test kitchen for years.) It’s a bit of an investment, but one we think is worth it.

The diminutive Work Sharp Culinary E2 outperformed every other sharpener in its price range. It’s great for the occasional cook.

If you’re an occasional cook and don’t have a lot of knives to maintain, we recommend the electric Work Sharp Culinary E2. It’s not nearly as fast, powerful, or sturdily built as the Chef’sChoice Trizor XV, but it’s easy to use, and it produced a better edge than any other sharpener in its price range. If you know you’ll need a sharpener only a few times a year, we think it will give you the best bang for your buck.

The Idahone Fine Ceramic Sharpening Rod works on any kind of knife (except a serrated one), and it’s gentler on blades than traditional steel honing rods.

A honing rod is the best and easiest way to maintain a knife’s edge between sharpenings, and the Idahone Fine Ceramic Sharpening Rod (12 inches) stood out among the nine models we tested. Its exceptionally smooth surface was gentler on the blades than the other rods were, and it worked equally well on Japanese- and German-style knives. Its maple handle was the most comfortable and attractive, and the Idahone comes with a sturdy ring for hanging (which is handy, since ceramic rods are vulnerable to chipping if stored in a drawer).

I’ve been sharpening pocket knives on an Arkansas stone since I was 9 years old, and I’ve been keeping my main cooking knife, a santoku, shaving-sharp for nearly 20 years using waterstones and an antique razor hone. I truly appreciate a fine edge, and stones produce the very finest. But I’m also a fan of “good enough,” and so for the past decade, I’ve also used an electric sharpener on my cheap, stamped-steel paring knives and on my expensive, forged-steel heavy chef’s knife. Though they’re not quite as good as stones can be, the best electric sharpeners produce excellent edges, and they do so in a fraction of the time. In short: I’m not one of those knife geeks for whom nothing less than an atom-splitting blade is acceptable. The defining characteristic of a sharp knife is that it cuts neatly, easily, and safely—and there’s more than one way to achieve this.

If you own a knife, you’ll eventually need to resharpen it. You can pay for a knife-sharpening service, you can use a sharpening stone, or you can use a manual or an electric knife sharpener—the kind we’re reviewing here. We like these sharpeners because they’re more reliable (and handier) than knife-sharpening services, and they’re far easier to use than stones. That means you’ll be much more likely to keep your knives sharp, and that then means your cooking will be more enjoyable and ultimately safer. A dull knife is a dangerous knife.

We also highly recommend that you use a honing rod (also known as a honing steel, knife steel, or sharpening steel). These are not sharpeners, although they’re often thought of that way. Rather, they help keep a blade’s edge keen between sharpenings by straightening out the tiny dings and dents caused by everyday slicing and chopping. Honing is a simple and fast process—it takes just a few seconds—and it can extend the life of a sharp edge for weeks or even months. For that reason, we consider them an essential tool for cooks. (Check our guide to chef's knives for tips on how to use a honing rod.)

For this guide, we focused on manual and electric sharpeners that use abrasives to put a sharp edge on knives. Our past tests showed the best of them to be safe and easy to use, capable of creating a truly excellent edge, and effective on knives of multiple sizes and styles.

This means that we eliminated three other types of sharpeners right off the bat: carbide V-notch sharpeners, sharpening stones, and jig systems.

Although manual and electric sharpeners come in multiple sizes and designs, we wanted all of our contenders to share a few characteristics:

Easy to use: Multiple factors affect how simple or difficult a sharpener is to use. Electric models have a powerful motor that sharpens knives quickly and without straining. Manual and electric sharpeners both have built-in guides to help you orient and keep the knife at the correct angle. Later in our testing, another factor revealed itself: the quality of a detailed instruction manual (or lack thereof).

Creates a very sharp edge—along the entire blade: Not all definitions of “sharp” are equal, and ours is probably on the strict end of the spectrum. So to level the field, we looked for sharpeners that could consistently produce knives capable of slicing a ripe tomato in one swift stroke, without sawing, tearing the skin or flesh, or having to press down hard on the blade. We also looked for sharpeners that created a consistently sharp edge from one end of the blade to the other. Depending on what you’re cutting, you’ll use the heel of the blade (near your hand), the tip, or the whole thing.

Able to sharpen multiple kinds of knives: Almost every kitchen will have a few different types of knives—at the very least a chef’s knife and a paring knife, and often a slicer, a boning/filet knife, and a carving knife. We looked for sharpeners that could handle all of them, and for ones that, more broadly, would work equally well on thin, thick, long, and short blades. We did not prioritize the ability to sharpen serrated knives—generally they don’t need sharpening, because they use teeth rather than pure keenness to cut—but we didn’t dock points for it, either.

One thing we didn’t give any weight to was whether a sharpener was German-style versus Japanese-style, or whether a sharpener offered both options. In the past, European-style knives were made of softer steel and sharpened at around a 20-degree angle, while Japanese-style knives were made of harder steel and sharpened at a more acute (“sharper”) 15-degree angle or so. This distinction no longer holds: The modern alloys now used by knife makers worldwide are generally tough enough to support acute edges, regardless of how hard they are. Indeed, iconic German knife maker Wüsthof now puts a 14-degree edge on its forged European-style blades—more acute than many Japanese knife makers use.

These criteria narrowed our list of contenders considerably. Then we spoke with representatives for several of the remaining contenders to get a better understanding of their technologies.

To test knife sharpeners, you need dull knives. We purchased our top pick chef’s knife, the Mac MTH-80, and our former budget pick, the Wüsthof Pro 4862-7/20 (now discontinued). Then we destroyed their razor-sharp factory edges. First we chipped and bent the edges by chopping and sawing on 80-grit sandpaper for two minutes; then we rounded and dulled whatever edge was left by sawing, scraping, and twisting the blades on 220-grit sandpaper for another two minutes. We repeated this process after every test, to ensure that all of our sharpener contenders faced an equal challenge.

Both of our knives arrived sharp enough to cleanly slice the tomatoes with virtually no downward pressure on the blade—their weight alone was enough. We took that as a benchmark for the sharpeners’ performance: With their tough skins and soft interiors, tomatoes quickly expose poor-quality edges. Dull knives will squish them rather than slicing them, and coarse or uneven edges can tear the skin. So to judge the quality of each sharpener’s performance, we dulled the knives, resharpened them, and then sliced through pounds of plum tomatoes.

We followed each sharpener manufacturer’s instructions carefully. Since we completely destroyed the knives’ edges before each test, we first operated the sharpeners on their “reshaping” setting, which forms a whole new edge on a knife by rapidly removing metal with high-speed or coarse abrasives. Then we completed each contender’s sharpening and (when an option) honing operations, in which the new edge is refined using slower speeds and/or finer abrasives.

In addition, we tested our contenders (minus the sandpaper torture) using the Wirecutter kitchen’s knives and those of multiple Wirecutter staffers—more than a dozen knives overall, including chef’s knives, paring knives, and boning knives of various sizes, ages, and states of disrepair. This gave us a sense of how versatile each sharpener was in terms of knife type, and it also forced the sharpeners to work intensively, potentially revealing inadequate motors or other weaknesses.

In a separate test, we looked at nine honing rods. Honing rods are used to maintain a knife’s edge in between sharpenings; in effect, honing repairs minor damage to the edge that comes from everyday use. Our methodology for picking, test protocols, and results are combined in the honing rod section of this guide.

The Chef’sChoice Trizor XV is reliable, fast, and easy to use, and it puts a razor edge on almost any kind of knife.

The Chef’sChoice Trizor XV, an electric sharpener, produced the keenest and most consistent edges of all the knife sharpeners we tested. And it did so more quickly and reliably than any other sharpener. Because of the design, it’s virtually impossible to make a mistake, even if you’ve never used a knife sharpener before. It repeatedly brought both of our test knives—one of them a $30 German workhorse, the other a $150 Japanese thoroughbred—back from dead dull to razor sharp. Its comprehensive instruction manual explains each step clearly, and its notably sturdy construction suggests that you can expect many years of performance.

Above all, the Trizor XV is our pick because of its ability to dependably return badly dulled knives to an extremely sharp edge. Even after we destroyed the knives’ edges with sandpaper, the Trizor XV repeatedly sharpened both the inexpensive, stamped-steel Wüsthof and the pricey, forged-steel Mac back to factory-new condition—despite their being made of different alloys and having different blade geometry. (Note: XV stands for 15 degrees, the final angle at which the Trizor XV sharpens. Trizor refers to the three progressive facets—rough, medium, and fine—created by the machine’s three sharpening wheels.)

Also important, the Trizor XV sharpened the blades evenly from heel to tip, leaving no dull spots. We got uneven sharpening—with the tip not as keen as the rest of the blade—in several tests of the similarly priced (and now-discontinued) Work Sharp Culinary E3, the Trizor’s closest competitor in our trial.

The Trizor XV sharpens knives fast. From start to finish, it took us a maximum of 4 minutes to bring an 8-inch knife from a sandpaper-dulled state to a like-new edge. Following the instructions, we found that every “pull” of an 8-inch blade through the sharpener took between 5 seconds (on the coarse abrasive) to just 1 or 2 seconds (on the fine “stropping/polishing” abrasive), and the total number of pulls topped out at around 30. By contrast, on the Work Sharp E3, it took at least 5 minutes to sharpen an 8-inch knife, and often longer. The total number of pulls sometimes topped out lower, at around 20, but because every pull took about 8 seconds, when going by the instructions, the total time was greater. And on badly dulled knives, we sometimes ran to 30 pulls on the Work Sharp E3, which took about 8 minutes. (If you’re running the numbers and coming up short, bear in mind that resetting the blade for each pull, and intermittently testing the edge, adds considerably to the total time elapsed.)

One reason the Trizor XV produces consistently sharp knives is its design, which makes it virtually impossible to mess up the sharpening process. When sharpening by any method, it’s critical to hold the blade at a consistent angle: If you don’t, the result is a rounded-over, dulled edge, rather than a sharp one formed by the apex of two consistent bevels. Like most electric sharpeners, the Trizor XV uses rigid, angled slots to help orient the blade. But it adds a feature that others lack: spring-loaded guides inside the slots that grip the blade at the correct angle and keep it from shifting around during the sharpening process. The Work Sharp E3—again, the nearest competitor in our test—doesn’t have an equivalent mechanism. Instead you have to manually set the blade’s angle in the slot and then manually maintain that angle as you slowly draw the blade through the sharpening element. In our testing, despite taking great care, we found it easy to slip up by starting the blade at the wrong angle or shifting it midstream (because the slot provides wiggle room), or having the blade snag in the slot and skid sideways into the belt. (Details on the E3 appear below, in the Competition section.)

The Trizor XV’s owner’s manual is another of this sharpener’s strong points. Once you’ve used any decent sharpener a few times, you’ve got the hang of it, but the Trizor’s detailed manual helps minimize mistakes from the get-go. By contrast, the manuals from Work Sharp Culinary (for all four models we tested) are more basic and would benefit from additional detail.

Finally, the build quality of the Trizor XV stands out. It’s a heavy, sturdy piece of equipment, weighing 4 pounds, 2 ounces, and equipped with a 125-watt, 2.1-amp motor. The Work Sharp E3 feels lightweight in comparison, at 1 pound, 10 ounces, with an 8.5-watt, 0.7-amp motor. Our 2016 test model Trizor XV has stood up to years of use in the Wirecutter kitchen, and after our formal tests of the 2019 unit were finished, we used it to sharpen more than a dozen staffers’ knives, running it for up to 30 minutes at a time. It’s not cheap, but if you spend a lot of time using your knives in the kitchen, we believe it’s a worthwhile investment. (Note: The third-stage “stropping/polishing” discs will, by design, eventually clog with metal debris from knives; they can be resurfaced with an included mechanism or replaced entirely.)

The diminutive Work Sharp Culinary E2 outperformed every other sharpener in its price range. It’s great for the occasional cook.

If your knife-use situation is undemanding—if you don’t cook a ton, don’t have a lot of knives, or just don’t need the absolute best sharpener—we recommend the relatively inexpensive, electrically powered Work Sharp Culinary E2 Electric Kitchen Knife Sharpener. It’s not nearly as powerful as the Trizor XV—and not nearly as fast. But it produces a very good edge, one that’s notably better than those produced by other similarly priced sharpeners we tested.

The soda-can-sized E2, the smallest and simplest of Work Sharp Culinary’s models, uses flexible abrasive discs to sharpen knives, and it has a manual hone that employs smooth ceramic wheels to polish the blade’s edge. Like its “big brother,” the Work Sharp E5-NH (see The competition), the E2 lacks the Trizor XV’s spring-loaded guides in the sharpening slots, so you have to keep the knife aligned yourself. But the simple design of the E2’s sharpening slots makes this fairly easy: Their sides are parallel, and the gap between them is small, so you really can’t badly misalign the blade. The sides of the E5-NH’s slots are nonparallel, and the gap between them is wider, so it’s fairly easy to get the alignment wrong or to wiggle the blade while sharpening.

Though the E2’s electrical motor is noticeably less powerful than the Trizor XV’s, we still found it capable of sharpening both the inexpensive, stamped-steel Wüsthof and the pricey, forged-steel Mac to a good edge. But because of the weaker motor, sharpening with the E2 took a long time, almost 10 minutes—versus about 4 with the Trizor XV. In all fairness, this sort of sharpening—where you take a completely ruined edge and create a brand-new one—is usually a once-in-a-knife’s-lifetime operation. Thereafter, if you take reasonable care of your knife, a quick touch-up every few months will be enough. That’s the sort of sharpening the E2 is best suited to.

A fairer comparison for the E2 is the manually operated Chef’sChoice ProntoPro 4643, which typically sells for $50, similar to the E2’s price. The ProntoPro—a former pick—uses ceramic discs to cut a pretty rough, sawlike edge into a blade (we’re talking microscopic “sawteeth,” to be clear). That sort of edge works quite well for coarsely slicing up food, just as the teeth on a wood saw are good at ripping through wood. In contrast, the smooth edge made by the E2’s fine abrasive discs and honing wheels produces neater slicing cuts that take less effort. We were even able to easily peel an apple with a paring knife sharpened by the E2—something only a very sharp knife with a smooth edge can do.

The E2 suffers from one irritating shortcoming. It has a built-in timer that shuts it off after 50 seconds of sharpening (40 seconds on the fast “reshape” speed, 10 on the slow “sharpen” speed). This is meant to keep you from over-sharpening, but in practice it’s not enough time to resharpen even a small paring knife, and not nearly enough to reshape a very dull chef’s knife. And so you wind up repeatedly turning the machine back on, cycle after cycle, until your knife is sharp. It took us about 10 minutes and 50 “pulls” through the E2’s abrasive wheels—25 pulls of 8 seconds each per blade side, plus the time it took to check and reset the blade between pulls—to get a good edge from a sandpaper-destroyed one. (For a blade that was dulled by normal kitchen use, we found 10 to 14 pulls, or a total of 3 to 5 minutes, to be sufficient.)

The Idahone Fine Ceramic Sharpening Rod works on any kind of knife (except a serrated one), and it’s gentler on blades than traditional steel honing rods.

As we explained above, a honing rod won’t sharpen your knife, but it will help keep the edge keen between sharpenings, so we think it’s good for most cooks to have around. After testing nine honing rods, both steel and ceramic, we think the Idahone Fine Ceramic Sharpening Rod (12 inches) is the best for most kitchens. It rapidly restored the edges of all the knives we tested, yet it was gentler on blades than the other rods we tested. It also removed less material from the blades than its competitors, something that will help to prolong a knife’s working life.

We used all of the honing rods on multiple knives, including our top pick for chef’s knives. To dull them between tests, we repeatedly sawed through 1-inch-thick hemp rope, a classic challenge used by knife makers to demonstrate their blades’ durability. We focused on 12-inch rods over 10- or 8-inch models because a longer rod is more versatile and easier to use: It offers more room to sweep the length of a standard 8- or 10-inch chef’s knife (and anything smaller).

We gravitated toward the ceramic rods. They all brought the edges of both the vintage Wüsthof (which is made of relatively soft steel) and the modern Mac (which is made of hard steel) back to a keen edge. And they provided a very slight friction when honing, which made it easy to sweep the blades in smooth strokes, as you’re supposed to. By contrast, the steel hones felt slick—the blade wanted to slip over instead of slide against the hone—and tended to chip hard, modern blades.

The Idahone was noticeably finer than the other ceramic rods, and it achieved the same or better honing with less abrasion. It further distinguished itself with a couple of fine details: Its ergonomic maple handle is more comfortable than the synthetic handles on the rest of the competitors, and its hanging ring is amply sized and made of sturdy steel. The other ceramic rods we tested had smaller hanging rings, plastic rings, or no hanging ring at all. (We recommend hanging any ceramic rod, because the material is somewhat brittle and can chip or break if it gets jostled around in a drawer or utensil holder.)

One of the only things we don’t like about the Idahone is its lack of a prominent finger guard where the rod meets the handle. You can still use it the “professional chef” way, holding the hone in one hand and sliding the blade toward it, but without a finger guard, doing so feels a bit dangerous. (We go into detail about honing techniques in our guide to chef’s knives.) As a result, we highly recommend using the safer “supported” technique for honing a knife, seen here:

Note that ceramic hones need occasional cleaning to remove knife metal particles that build up on their surface (they form a gray layer). Melamine foam sponges (like the Mr. Clean Magic Eraser or its equivalent) or mild abrasives, like Bon Ami or Bar Keepers Friend, will work well.

If you do want to take the leap into sharpening your knives by hand on a stone, I’d recommend water stones, and avoid oil stones. They’re easier to master, and less messy—as the name suggests, they use water as a lubricant, so they simply need a rinse under the tap to clean them once you’re done sharpening.

You’ll need two stones of two grits: a relatively coarse one for setting the edge, and a fine one for polishing it. A longer stone is easier to use, so I’d recommend 8” versions. The 1000/4000-grit combination stone from Norton is a great way to start out without breaking the bank, and comes with a stand that keeps your knuckles from bumping into the counter when sharpening. (I’ve kept my knives shaving-sharp for 20 years on a pair of 1000- and 4000-grit stones.)

There are many different ways to sharpen with water stones, and you can find them all on YouTube. It gets bewildering. I’ve always used a push-pull technique, shifting the blade after each stroke until I’ve sharpened it end to end, but after trying out a few other methods for this guide, I think the one recommended by Stella Culinary is a really solid way to get started. Placing the stone sideways lets you see the blade edge as you go, which helps you maintain a consistent angle. And using your hips rather than your arms to sweep the blade over the stone makes for a stable, consistent stroke. (One last note: I’d avoid using a honing rod afterwards. They can actually ding up that beautiful polished edge you’ve just created, and can chip hard Japanese-style blades.)

Finally, be ready for a learning curve. Wirecutter photo editor Michael Hession began using water stones in January 2021; when we spoke at the end of March, he still felt he needed more time to master the skill—but he had also brought his paring, filet, chef’s, and santoku knives to a satisfyingly sharp state. As of December 2021, after using his stone for nearly a year, Michael said the process has been rewarding and fun to learn on the whole. But he also noted that the amount of prep, labor, and mess involved is “not at all convenient.” And though he’s able to get his knives sharper than before, he’s still unable to achieve the “uber razor-sharp” blades he sees experts pull off in tutorial videos. He has yet to compare the sharpness he gets from his stone to any of the picks in this guide.

We tested the Work Sharp Culinary E5-NH Professional Electric Kitchen Knife Sharpener, which is an upgraded version of the now-discontinued Work Sharp Culinary E3, a popular and extremely well-reviewed sharpener. The E5-NH is capable of making an edge as sharp as the Trizor XV (they employ different sharpening mechanisms, though—the E5-NH uses flexible abrasive belts, and the Trizor XV uses diamond-impregnated ceramic discs). But we also discovered a few shortcomings that kept the E5-NH from becoming a pick. The Trizor XV incorporates spring-loaded guides that align the blade correctly in the sharpening slot, but the E5-NH lacks them—you have to carefully hold the knife against the slot’s sidewall. Additionally, the sides of the slot are not parallel, and if you slide the knife along the wrong side, you’ll be sharpening at an incorrect angle. The E5-NH also has an automatic timer function that’s more hindrance than help: It shuts off the machine every couple minutes, often in the middle of a sharpening session. These troubles are a shame, because when you do get the E5-NH to perform as intended, it can produce an exceptional edge.

The Chef’sChoice ProntoPro 4643, a former pick, costs about the same as the Work Sharp E2, but it produces a coarser edge. The E2 makes a finer edge that cuts more smoothly and with less effort.

A hybrid manual-electric sharpener, the Chef’sChoice Hybrid 210 uses a motor and abrasive wheels to grind the new edge and employs a manual stage to hone it. This sharpener is eminently affordable, but the Work Sharp E2 produces a better edge.

We looked at but did not test the Kai Electric Sharpener, a sharpener purpose-built for Shun knives, after a representative told us that the company strongly recommends that Shun owners send their knives back to the company for (free) resharpening instead.

We decided after long-term testing that the Brød & Taylor Professional Knife Sharpener, a former pick, is easy to misuse, which means blades could get damaged. When used correctly, it can quickly produce a sharp, honed edge. But a slight error in the angle at which you’re holding the knife can create an uneven bevel or strip away too much metal from the blade.

The well-reviewed McGowan Diamondstone Electric Knife Sharpener put a very nice edge on a test knife. It also threw off an alarming amount of dust, indicating that its grinding wheels were rapidly wearing down. That and the lightweight motor made us skeptical of its long-term performance, despite good reviews and a limited three-year warranty.

The Presto EverSharp 08800 electric knife sharpener gets great reviews. In our test, though, its flimsy motor instantly bogged down when our knife contacted its sharpening wheels—and even light pressure threatened to stop the sharpening wheels entirely. The high, wide guide frames meant it couldn’t sharpen the last ¾ inch of a blade, an unacceptable shortcoming. We’ll take our experience over the reviews.

We tested eight other honing rods alongside our pick. Three were ceramic: the Cooks Standard (12 inch), the Mac black ceramic (10.5-inch), and the Messermeister (12-inch). Five were traditional steel hones: three by Messermeister (fine, regular, and Avanta—the latter two have since been discontinued), a dual-textured fine-and-smooth “combination cut” Victorinox, and a Winware, all 12 inches in length. With one exception, we set a top price of about $40, which eliminated the professional-grade steels made by Friedrich Dick; these are standard in the butchering trade, but few home cooks need their extreme durability and specialization. As our top pick did, the three ceramic rods here offered a slightly grippy surface that made it easy to slide the knife blades smoothly along their length, which is key to good honing. But all were somewhat coarser than the Idahone, so the Idahone was less abrasive to the blades. Also, the Idahone’s generously sized steel hanging ring is superior.

This article was edited by Marguerite Preston.

Tim Heffernan is a senior staff writer focusing on air and water quality and home energy efficiency. A former writer for The Atlantic, Popular Mechanics, and other national magazines, he joined Wirecutter in 2015. He owns three bikes and zero derailleurs.

Should I use an electric sharpener on my expensive chef’s knife?

The Chef'sChoice Trizor XV is the best knife sharpener we’ve found: It’s easy to use, durable, and puts an exceptional edge on many types of knives.

We’ve tested 24 chef’s knives, chopping over 70 pounds of produce since 2013, and we recommend the Mac MTH-80 since it’s sharp, comfortable to use, and reliable.

by Tim Heffernan and Lizzy Briskin

We sliced through pounds of steak, chops, and chicken to find a set of steak knives that’s sharp, stylish, and doesn’t break the bank.

Ceramic Knife Wirecutter is the product recommendation service from The New York Times. Our journalists combine independent research with (occasionally) over-the-top testing so you can make quick and confident buying decisions. Whether it’s finding great products or discovering helpful advice, we’ll help you get it right (the first time).