Director of ophthalmology at Mitsui Memorial Hospital. Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1957. Graduated from Jichi Medical University. Following his medical residency, joined the University of Tokyo’s Department of Ophthalmology. Practiced at institutions including the Japanese Red Cross Musashino Hospital before joining the staff at Mitsui Memorial Hospital, where he has been in his current position since 1992. Developed the breakthrough “phaco prechop” technique for cataract surgery, which is currently used at hospitals in 66 countries.

Dr. Akahoshi Takayuki is always on the run in the hospital. Instead of walking, he dashes from place to place to save time. On the day of our interview alone, he performed close to 60 cataract surgeries—a normal number, he says. He is able to perform so many operations every day thanks to his strong conviction and a revolutionary surgical technique that he developed himself. Barraquer Eye Speculum

“Cataracts are a condition where the lens in the eye goes cloudy, are a symptom of aging, like the graying of hair,” explains Akahoshi. “Removing the clouded lens and implanting a new intraocular lens will restore the patient’s vision. Artificial lenses have significantly improved, so that astigmatism and presbyopia, or age-related farsightedness, can now be corrected as well. Patients are often surprised by how clearly they can see after surgery.”

Akahoshi notes that while cataracts can be cured with surgery, they remain the most common cause of blindness around the world. “Many of those with this condition don’t have access to treatment,” he says. But this is something he is working to change.

The standard procedure for cataract surgery is to cut a tiny hole in the cellophane-like membrane surrounding the lens, insert a metal tip that vibrates at ultrasonic frequency to fracture the lens’s nucleus, draw it out of the eye, and insert a new intraocular lens in its place. The nucleus hardens with age. The key is to remove it quickly through the tiniest possible incision without ripping the thin membrane. A large incision can distort the eye, leading to astigmatism, and the longer the procedure takes, the higher its chances of damaging the cells of the cornea or causing a bacterial infection.

The most widely used technique of fracturing the nucleus is known as “divide and conquer.” Developed by Dr. Howard Gimbel of Canada, it involves carving cross-shaped grooves into the lens using ultrasound and dividing the nucleus into quarters to facilitate removal. However, as Akahoshi notes, “The divide-and-conquer technique isn’t foolproof. If the grooves are too shallow the nucleus won’t break neatly into quarters, and if you engrave too deeply you could pierce the membrane.”

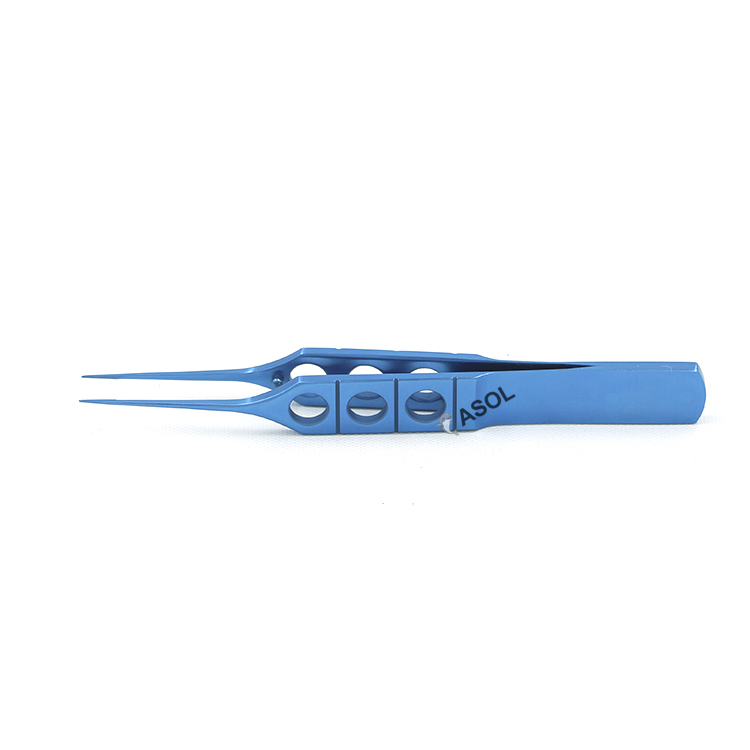

The challenges of this technique got him wondering if there wasn’t an easier and more reliable way of dividing the nucleus. “One day, about twenty-seven years ago, it hit me: Maybe I could break the nucleus by inserting a pair of sharp forceps vibrating ultrasonically and opening the jaws of the forceps inside the nucleus.”

Akahoshi promptly set out to develop ultrasonic forceps. But he had no funds, being a poorly paid hospital doctor, and he could not find corporate backing. So he decided to look for an existing device that could serve as an effective substitute.

After considering various possibilities, he eventually came across jeweler forceps. “These forceps have very sharp tips,” he says. “I thought they’d work. During surgery, I pressed an ultrasonic tip against the forceps as I inserted them into the nucleus, and they slid right in. When I opened the jaws, the nucleus split cleanly into pieces. It only took a few more seconds of ultrasonic vibration to further break the pieces into tiny fragments, and sucking them out was simple. This was it!”

Akahoshi says he still remembers his body trembling at the success. In subsequent testing, he found that the forceps can split the nucleus even without ultrasound if the cataract is not at an advanced stage.

In 1992 the Japanese doctor succeeded in developing a safe, reliable, and quick way of performing cataract surgery by mechanically splitting the lens nucleus prior to emulsifying the lens with ultrasound and extracting it from the eye. He named the technique “phaco prechop,” where “phaco” refers to the lens of the eye. The time required for surgery was slashed from 20–30 minutes to 5 minutes or less. This also dramatically reduced the frequency of postoperative complications.

The “prechopper” Akahoshi uses in his cataract removal technique.

A close-up view of the tip of the prechopper.

Akahoshi would go on to develop the tools and techniques for removing the clouded lens and implanting an intraocular lens with a diameter of 6.0 millimeters through a 1.8-millimeter incision. “My new method reduced the scar length from 3.2 millimeters to 1.8 millimeters,” he explains. “This had important implications for preventing surgically induced astigmatism, as the chances of developing the condition after surgery are roughly proportional to the cube of the incision length. A 1.8-millimeter scar is small enough to heal on its own, and the shape of the cornea is largely unaffected.” In 2004, he had finally developed a method of cataract surgery that would not cause astigmatism.

Because of its revolutionary nature, though, Akahoshi’s new surgical procedure ran into unexpected resistance. Some members of the Japanese medical community expressed fears that the shortened surgery time might inspire the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare to lower the medical service fee that doctors receive for cataract surgery. Akahoshi says he came under pressure to refrain from telling reporters that the operation can be done in five minutes and to say instead that it takes four experienced doctors an hour to perform.

Akahoshi would not give in, though. “Other doctors insist that patients undergoing cataract surgery have to be hospitalized, but surgery using the phaco prechop technique can be done as an outpatient procedure.” Many cataract patients are in their fifties or older, he notes, an age group that prefers not to stay in the hospital if avoiding it is possible. “So I’ve continued to perform outpatient surgery without giving in to any kind of pressure.”

Dr. Akahoshi performing cataract surgery. His procedure takes less than five minutes.

Over the quarter century since Akahoshi invented the phaco prechop technique, he has gradually won over supporters with his unwavering stance. Today some 1,800 private physicians in Japan refer their cataract patients to Akahoshi. At Mitsui Memorial Hospital, where he works, the annual number of cataract operations can be as high as 7,200. Akahoshi operates at other hospitals as well, and in 2015 he conducted more than 10,000 operations in total.

In 1996 he displayed his technique to a global audience when he performed live surgery at the invitation of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the world’s largest international association of eye doctors. “I was the first Japanese surgeon to do so,” he smiles. “Images from my surgical microscope were transmitted live via satellite and projected on a large screen at the academy’s annual meeting as thousands of physicians and surgeons looked on. When I finished, they all rose and gave me a standing ovation. My procedure had won their approval as a breakthrough in cataract surgery.”

After this, Howard Gimbel invited Akahoshi to Canada, where he again performed live surgery for a professional audience. “This was despite the fact that my technique could in some ways be seen as discrediting his. I was impressed by his magnanimity.”

Akahoshi is often invited to perform surgical demonstrations for academic conferences overseas. Live images of the procedure are screened at the conference venue.

Every year Akahoshi receives invitations from numerous countries to give live surgical demonstrations and talks. He has visited 66 countries to date. This has given him some surprising insights into the medical conditions he tackles. “Cataract symptoms vary between countries and regions. In countries near the equator and other places that are subject to strong ultraviolet radiation, for example, the lens nucleus can become as hard as a rock. Removing a hardened lens using conventional techniques takes time, increasing the risk of complications.”

With Akahoshi’s phaco prechop technique, though, since the nucleus is mechanically fractured prior to extraction, the procedure can be performed quickly and safely. “Phaco prechop is becoming the preferred method in a growing number of Latin American countries, including Brazil and Mexico,” he explains with pride.

In every country that he visits, Akahoshi is happy to share his surgical techniques in full detail—on one condition: Surgeons whom he instructs must not keep what they learn to themselves but must pass on that knowledge to their colleagues. He has not patented the surgical instruments that he designed, because prices can be kept down if different local manufacturers produce them in their respective countries, thereby making them more widely available.

In 2017 Akahoshi won the tenth Kelman Award, presented biannually by the Hellenic Society of Intraocular Implant and Refractive Surgery, for his innovative surgical techniques and his dedication to teaching and disseminating them.

Akahoshi conducts a live demonstration of cataract surgery in Pakistan.

02>Lacrimal Probes “I’d like to save more people in developing countries from losing their eyesight,” he says. “The way to do that is to make the best treatment available at the lowest cost. That’s why I want to continue polishing and sharing my current surgical techniques. Whatever pressure may come my way, I won’t be daunted.”