Trials are under way to find advanced solutions to a notoriously difficult problem. But could a focus on recycling distract from other issues?

I n a warehouse in Melbourne’s south-west, plastic confetti is being liquefied. Amid the whirring and beeping of machinery, a table displays shredded soft plastics – colourful flakes of empty chip packets, bin liners and transparent bread bags. The mound sits beside two jars of oil – that’s what the plastic will become. One is light, like olive oil. The other is as dark as tar. Functional Material

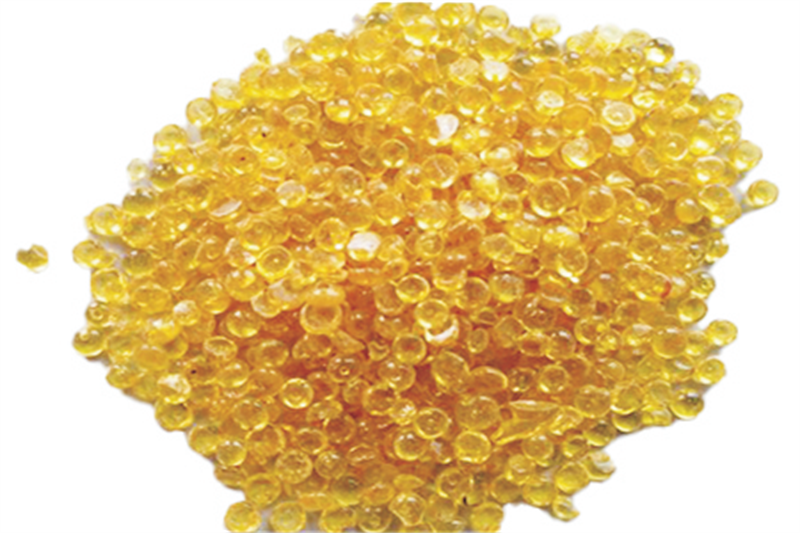

The goal, says Logan Thorpe, a special projects manager at APR Plastics, is a “closed loop” of advanced recycling. Plastic waste is turned into oils, which are made into clear pellets that resemble granules of rock salt, which can then be used to produce more plastic.

There is a synthetic, but not unpleasant, smell in the air. In an open shipping container, a shredder tears soft plastic into 10-15mm-sized flakes. These are fed through a dryer and then an extruder, a machine that heats the flakes into a consistency that Thorpe describes as “a hot gum, like a sausage almost”. Finally, the plastic undergoes a process known as pyrolysis – it is heated without oxygen, to temperatures up to 500C, which yields two types of oil, some gases and char – an ashy carbon residue.

The machine is a prototype capable of processing up to one tonne of soft plastics a day, Thorpe says. Early next year, APR will upsize to a commercial machine that can handle five tonnes a day, with a corresponding daily output of about 5,000 litres of oil. APR sends the oil to a partner firm, to process it into pellets.

In November, the federal government signed up to the international High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution, which aims to recycle or reuse all plastic waste globally by 2040.

Australia has also set a goal of making 70% of plastic packaging recyclable or compostable by 2025. At current rates, it is unlikely to hit that target. A report published last year by the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation (Apco) found that in 2020, just 16% of plastics were recycled. The rate of soft plastic recycling was even lower: 4%.

The advanced recycling trial in Melbourne is part of the national plastics recycling scheme (NPRS), a soft plastics program led by the Australian Food and Grocery Council. The NPRS aims to recycle 190,000 more tonnes of plastic a year – about a third of the soft plastic waste that currently goes to landfill.

Trials are under way until March in six local government areas in Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia. The program involves kerbside soft plastic collection, and is unaffected by the suspension of REDcycle, which until its collapse was Australia’s largest consumer soft plastics scheme, with collection points in nearly 2,000 stores.

“It’s no secret that soft plastic has posed a particular challenge due to the complexity of its collection and in finding sufficient end markets for reprocessing,” Apco’s chief executive Chris Foley says. “While the REDcycle system provides an effective solution for the first part of this problem, the recent pause in operations was largely due to a lack of end markets for this material. This is a key challenge for the industry to work through.”

Throw an empty milk carton or ice-cream tub into kerbside recycling, and where does it go? The contents of your bin are taken to a materials recovery facility, where mixed recyclables are separated by various machines into different streams: aluminium, cardboard, plastics and so on.

Plastics are then taken to specialised facilities or shipped overseas. Much of Australia’s plastic was exported to China until 2018, when it stopped accepting foreign waste. Other countries, mainly Indonesia and Malaysia, have since borne the brunt. In 2020-21, Australia exported 124,000 tonnes of scrap plastics – down from an annual peak of 203,000 tonnes in 2015-16. Since July, the export of mixed plastics has been banned.

At present, virtually all plastic that is recycled commercially goes through mechanical recycling – melting waste into an amalgam of plastics which are then reformed into new items such as bollards.

Most soft plastics are made of polyolefins – a group of polymers including polyethylene and polypropylene. Soft packaging usually contains multiple layers of different plastics, combined to create specific qualities such as strength or an oxygen barrier to extend the shelf life of food products.

Soft plastics are difficult to recycle because they interfere with mechanical recycling machinery, says Dr Deborah Lau, who leads the CSIRO’s Ending Plastic Waste mission. “The inability to recycle soft plastics easily with mechanical recycling isn’t because of their chemical nature, it’s actually because of the physical form.”

The trials under way at APR are an example of advanced – or chemical – recycling.

“The heat and absence of oxygen breaks down polymer chains into smaller building blocks,” Lau says. “That produces a liquid which is a mixture of small hydrocarbon molecules [the main components of crude oil]. Those molecular building blocks can be separated and then used as the basic feedstock to create new – what are called ‘virgin’ – plastics.” (Globally, about 99% of plastics are derived from fossil fuels.)

Plastic pyrolysis is operating at commercial scale overseas, including in Europe and the US. In March, the US waste management firm Brightmark announced it was building a plant in the NSW town of Parkes, which it said would be able to process 200,000 tonnes of plastic waste annually. “Pyrolysis is not new technology,” Thorpe says. “It just hasn’t been perfected in energy efficiency and producing quality oil until now.”

Sign up to Five Great Reads

Each week our editors select five of the most interesting, entertaining and thoughtful reads published by Guardian Australia and our international colleagues. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Saturday morning

The technology is controversial: some critics have called it a greenwashing tactic that misleads the public into believing more plastics are being recycled than is actually the case. A US report published in May found that since the emergence of advanced recycling in 2018, plastic recycling rates in the US had dropped from a peak of 9% to less than 6%.

Others have criticised the focus on plastic waste as distracting from the existential threat of the climate crisis. Researchers have pointed out that plastic is less of a threat to oceans than climate change or overfishing.

Generating high temperatures requires high energy input, and pyrolysis is not emissions free – some gases are produced in addition to the crude oils, which can be burnt to power the heating process. But life cycle analyses, Lau says, have shown that fewer emissions come from plastic recycled through pyrolysis than virgin plastic, “because the carbon is actually being recirculated, it’s not coming from fossil fuels”.

Alternatives to pyrolysis include hydrocatalytic decomposition – which heats plastic with water, in the absence of oxygen – a technique used by the Australian firm Licella, which last week announced a partnership with the global packaging company Amcor for a proposed advanced recycling facility in Melbourne.

Even with advanced recycling, plastic is not infinitely recyclable, says Prof Kalpit Shah, a chemical engineer at RMIT. There comes a point after multiple cycles at which it reaches an “end of life” stage.

“Over time, it may lose its mechanical strength or certain chemical or physical properties,” he says – the result of impurities, for example. At this point, it cannot be recycled into more plastic, but can be used in applications including roads, tiles and steel.

Some say a focus on collection and recycling does not go far enough to address plastic waste. Dr Anya Phelan of the University of Queensland has called for measures such as “extended producer responsibility” – regulations that would require plastics manufacturers to pay for the recycling and disposal of their products.

In the hierarchy of waste minimisation strategies, “the first priority is really around overall reduction of plastic waste use,” Lau says, “where, if it’s possible, unnecessary plastics can be phased out”.

“The fact that there has been such a strong reaction to the pause in the REDcycle system really shows that there’s an enormous appetite for soft plastic recycling to support mechanical recycling,” Lau says.

Polycarbonate/polypropylene (PC/PP) Film/Sheet (Casting) “The reaction to the pause … has been a really positive step in bringing people’s attention towards understanding how the plastics recycling system works.”