Your browser does not support the audio element.

Thirteen years on, that case at the Aocheng Chemical Plant still bothers me, poking and prodding somewhere deep down inside of me, like a riddle that I’ll never figure out. It was during a bright midday at the plant. The workers carried their lunch boxes out to the edge of the fissured concrete lot. They talked amongst themselves: Everything was fine last night, and today, it’s gone. When Sergeant Zhao Dezhong arrived from Aocheng Police Station with two cadets in tow—Xiao Li and I—we saw a heavy-duty cart sitting on the ground, with its two wheels missing. It felt incredibly unjust, like seeing a disabled man whose prosthetic limbs had been swiped from him. Welded Mesh Fencing

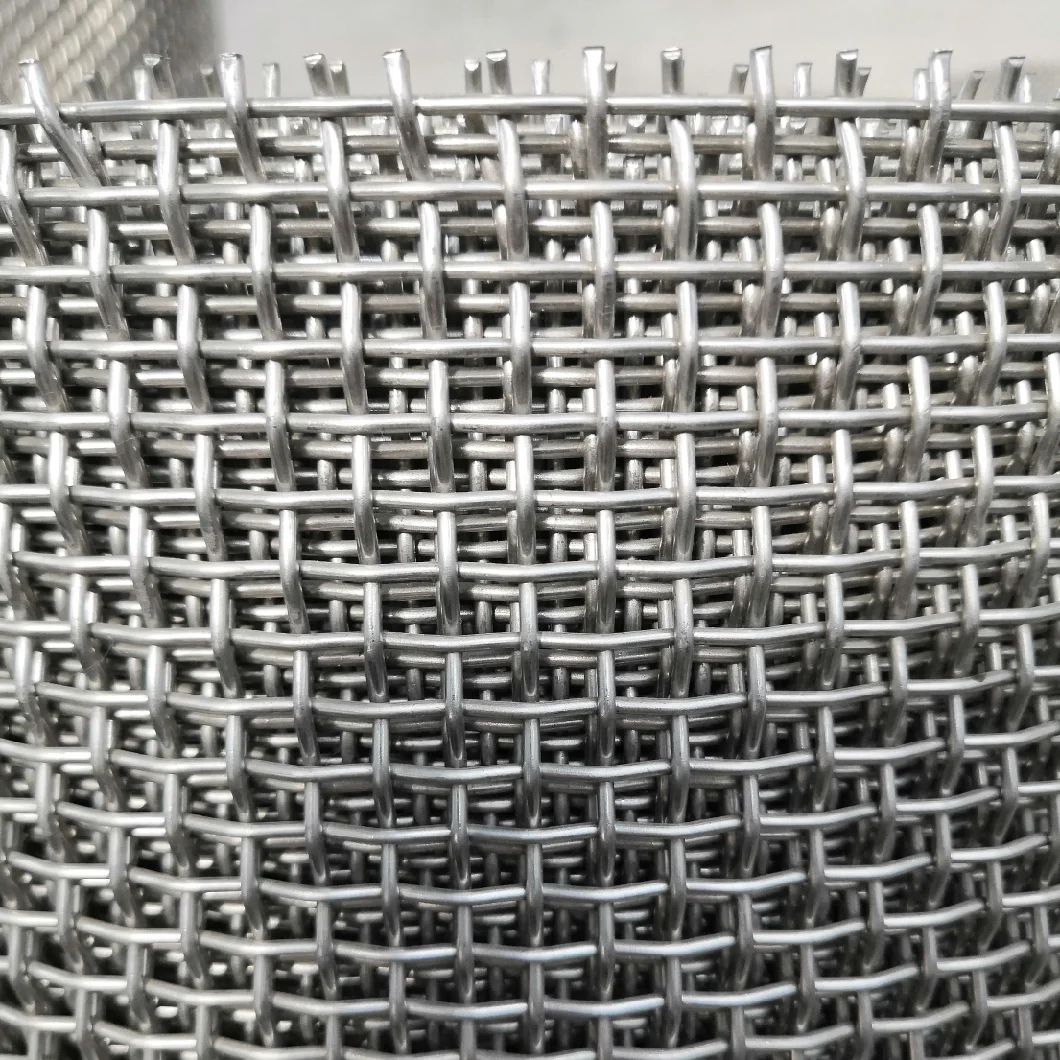

According to the head of security at the plant, stealing the wheels off the cart would have been as difficult as robbing a bank. There were meter-high walls around the entire plant, with another meter or so of razor wire mounted on top. The plant had only a single gate, manned around the clock by capable men. At night, security details patrolled the grounds. On top of that, at the time of the incident, there were still workers on site in brightly lit workshops.

“This is nothing less than a provocation!” said the head of security.

In the days when Sergeant Zhao had been a soldier in the reconnaissance corps, he had once turned a comrade-in-arms over to a military tribunal for pilfering important supplies. He quickly concluded that the theft at the plant was an inside job. The type of robber that moved around to look for marks would need to check the place before making their move, and they would have a difficult time assessing what might be available to steal in the plant, or even getting a general lay of the land. Furthermore, statistics showed that 65 to 80 percent of theft cases at industrial facilities were committed by the workers.

“Luckily,” Sergeant Zhao said, “everyone here lives in the dormitory, so no one has left the plant yet.”

We drew up a scheme with the head of security at the plant. He would call the workshop directors, who would call the section chiefs, who would then assemble the workers. Each group would be questioned in turn. There were only two questions: What were you doing between three and five in the morning? Do you have evidence proving you were sleeping or working at that time?

The answers that the workers gave were not particularly important. What was crucial was to observe their physiological reactions to the questions. Sergeant Zhao ordered Xiao Li and I to act as living polygraph machines, carefully observing the respondents’ actions. When the workers came in for questioning, their reactions were consistent: they glanced around the office, awkwardly trying to figure out where to put their hands, and steadfastly refusing to meet our gaze. Some of the men fell under suspicion because they were too young or had unconventional hairstyles, but they turned out to have solid proof of their whereabouts during the time of the theft. They said that Lao Wang would confirm their alibis. Lao Wang, an honest and straightforward man, told us that the men had all been working overtime that morning, and they had not left their stations even for a bathroom break.

“The fox is more cunning than the hound,” Sergeant Zhao observed. “They have better mental resilience, too.”

After the investigation, the head of security told us it was time to eat. Before Sergeant Zhao would eat, he wanted to make sure that none of the workers were allowed to leave the plant. The head of security assured him they would ensure nobody left. After that, we were led into a private dining room in the canteen. There were four dishes served in large basins, including one with fish, another with a whole chicken, and a soup with soft-shelled turtles floating on top. The head of security opened a bottle of liquor and pulled out a neatly folded bill of one US dollar from under the cap. “Whoever can drink me under the table,” he said to his subordinates, “will receive some American money.”

Sergeant Zhao protested that he wasn’t much of a drinker, but still pounded three glasses as the security chief insisted. He was soon drunk. “Alright,” he mumbled, “that’s enough for today. Let the workers go if they want to. Alert the night patrol to watch for the thieves trying to move the goods.”

We rushed to the plant the next afternoon. The head of security assured us they had kept a close eye on the plant grounds. Nothing suspicious had been spotted. Sergeant Zhao said that was good since it meant the culprits had not attempted to move the goods. After that, we began looking around the plant like someone looking for a lost set of keys—confident they would turn up somewhere. We believed they might be hidden under a broken machine or tucked beneath a tarpaulin on the edge of a cesspool. As we passed a utility shed, Sergeant Zhao jumped to look at the roof. He couldn’t jump high enough, so he told me to investigate. I couldn’t jump high enough either, so Xiao Li jumped to take a look. All he could see were some broken asbestos tiles.

We even considered the possibility that the thieves had taken the wheels up a tree, hidden within the branches and leaves. But we only discovered the nests of innocent birds up there. We were so wrapped up in disappointment that dinner passed in stunned silence. We didn’t hear a word the head of security said. Only the delicious oily food, left an impression, especially the fine dish of celtuce.

It was time to redirect the investigation. Back at the station, the aura of Sergeant Zhao’s “Outstanding Reconnaissance Soldier” award was beginning to fade as he got frustrated with himself. After a long time, he stopped grasping his hair and, in an exhausted weak voice, said: “The goods aren’t at the plant. If this was an inside job, we need to account for external involvement as well. We also need to consider whether or not this might have been an outside job.”

The next morning, we went to the plant but walked around the exterior wall instead of going inside. Weeds studded with dewdrops grew at the base of the wall. Sergeant Zhao told us to watch for places where the vegetation had been pressed down. The wheels weighed at least several dozen kilograms, so there would certainly be some sign of them being tossed over the wall. However, the morning’s search only turned up sanitary pads covered with dark, clotted blood, and a few rat carcasses that expelled clouds of flies when we approached. “Maybe the weeds have bounced back,” Sergeant Zhao said. “Let’s go over to the reeds.”

As we left the base of the wall and descended a road into the reeds, we entered a strange, shady, infinite otherworld, where our shoes were quickly covered in mud. As I walked, I felt my hunger increasing. I wondered if I might encounter a shrew popping out to wink at me. I had eaten them many times before since they were considered a delicacy in Aocheng. I saw a few holes in the swampy ground, but they were flooded. Wheels, wheels, wheels, I reminded myself, you must find the wheels. My attention began to wander again. Just as I was about to meander into the void, to stagger into the night, I saw Xiao Li’s backside floating out of the last sliver of light. He was taking a piss.

When it got dark, we turned and headed back toward the station. As we went, we caught sight of a figure standing on one of the ridges between the nearby paddy fields, waving with a flashlight in hand. As we approached, we saw that it was the plant’s head of security. “Thank you for your hard work,” he said. He shined the flashlight onto our shoes. “Look at those shoes,” he said anxiously, “covered in mud.”

“It’s nothing,” Sergeant Zhao said. “Anyone discouraged by this sort of hard work has no right to call themselves a police officer.”

Naturally, we returned to the plant for dinner. A deputy director of the factory came to join us. After we exchanged a few words, silence fell. The men from the factory became quiet because they felt sorry we had to go through so much trouble trying to solve a case at their plant, and we were quiet because we were eating free food and solving no crimes. Both parties broke the silence almost simultaneously. “We really thank you. We can’t thank you enough,” the deputy director blurted. “You see that we haven’t made much progress in the case,” said Sergeant Zhao.

The head of security stepped in: “Let’s eat!”

As we left the canteen after dinner, I saw a few gray-haired workers in filthy uniforms beating out a rhythm on their ceramic basins. It seemed like an old song that no longer made sense to my generation. As we passed, the sound died down, then picked up again as we walked out.

Back at the station, Sergeant Zhao sat on the sofa without changing out of his boots or washing up and sighed deeply. Before we could say anything, he stood up and called to us, “Quick! Get a flashlight. We’re going up the mountain.” Xiao Li and I weren’t happy. Our legs were sore and swollen from walking all day. Sergeant Zhao noticed us hesitating. “Fine,” he said, “I’ll go by myself.” At that point, we had no choice but to follow him.

There was some moonlight. We trudged through the weeds and reeds, shining our flashlights onto what seemed like a path with no end. Sergeant Zhao said: “You can imagine that the thief must have rolled the wheels down this trail. Look around for tracks. I don’t think he would have carried the wheels over his shoulder the entire way.”

We saw nothing. We only felt exhaustion. As we stumbled sleepily forward, Sergeant Zhao cried out, “I’ve got something here!” Gathering ourselves again, we crouched down to look. There were two parallel tire tracks, with a wavy intermittent pattern. It was exactly what we were searching for.

Sergeant Zhao beamed like a child. “He had to set the wheels down,” he said.

Our morale rose as we rushed forward for another five or six minutes before spotting an earthen hut. Beside the hut was a cart with an extra wheel next to it. Overjoyed, Sergeant Zhao went over to kick the door. The farmer inside woke up, switched on the light, and came to the doorway. We picked up the wheel and went into his hut to study it. The light was too dim to see, so we trained our flashlights on the wheel. There were three leather patches resembling ringworm scabs on the tire. It didn’t match the stolen wheel from the factory. But anyone could have made repairs like this as a disguise, just like a murderer will change their hairstyle to hide from authorities. Sergeant Zhao wanted to rip off the patches, but the farmer protested: “Don’t rip them off!”

Sergeant Zhao, hell-bent on pursuing justice, ignored him and went on trying to peel off the patches by hand. After a while, he was forced to take out his nail clippers to rip the patches off. He felt the places the patches had covered, then looked closely again at the tire. It appeared that the tire had really needed repairs. Sergeant Zhao wasn’t satisfied, however. He produced a pocket knife and enthusiastically plunged it into the tire. The sound of his work filled the hut. The tire deflated.

“This tire is falling apart,” Sergeant Zhao said. “You’ve done nothing wrong, and it belongs to you. Take it to the station tomorrow and I’ll have someone fix it up for you.”

On the way back to the station, I hung my arm over Xiao Li’s shoulder, and we walked together like two wounded soldiers. “It’s awfully strange,” we heard Sergeant Zhao say, “for something so big to just go missing. It’s strange. Disappeared, as if by magic...”

For the next several days, we stood guard at intersections and inspected junkyards. We even sent people to gather intelligence, but nothing turned up. We had lunch and dinner at the plant every day. After a week of freeloading, we felt bad and chose to stay at the station. But the head of security turned up and said he had prepared a banquet for us at Yuncui Restaurant. Sergeant Zhao blushed. “We can’t accept a reward that’s not deserved,” he said.

“A reward that’s not deserved?” the head of security said. ”You have already done a great deal for us.”

“What have we done?” Sergeant Zhao said. “A tire is worth fifty yuan. We’ve had just about two thousand yuan of food.”

“Don’t say it like that,” the head of security said. “It might only be fifty yuan today, but tomorrow it’ll be five thousand, then fifty thousand, then five hundred thousand. That’s a great amount of state property being lost.”

“We haven’t even figured out what happened to that fifty yuan, though,” Sergeant Zhao said.

“You have at least scared the criminals,” the head of security retorted.

“I won’t go to the banquet,” Sergeant Zhao said. “You can go ask the others.”

“I won’t leave until you agree to go,” said the head of security.

“Fine,” Sergeant Zhao said, “then don’t leave.”

The head of security went in to see the station chief. The chief paced his office with his hands clasped behind his back like the famously upright Song dynasty politician Bao Zheng. He listened to the head of security’s story, nodding and grunting, then shouted: “Zhao! Xiao Ai! Xiao Li! Get in here.”

When the four of us—Sergeant Zhao, Xiao Li, the chief, and I—arrived at the banquet at Yuncui Restaurant, a dozen dishes were already steaming on the table. A dozen men stopped cracking sunflower seeds and got up to greet us. The head of security introduced each of them: “This is Director Zhu, Director He, and…” The chief waved and interrupted him. “Thank you,” the chief said. “Thank you very much. We already know each other.”

The head of security directed the chief to another table, saying shyly, “And here are my wife and child. That is section chief Yang’s wife. Everyone came tonight.”

The commander reached out to shake their hands, greeting everyone.

In the end, Sergeant Zhao paid for a set of second-hand wheels out of his own pocket. He sent me and Xiao Li to bring them over to the plant. “Yes, these are the ones!” the head of security said when he saw the wheels. He pushed them out to the concrete lot excitedly. In the distance, we saw the cart that was still missing its tires. It reminded me of a heart-stricken woman waiting for her lover to return.

In my early twenties, I worked as a police officer in the most remote area of an inland province in central China. There, everyday events could all have been turned into thrilling fiction, but unfortunately, I didn’t realize such wealth at the time. In 2006, four years after leaving the police force, I picked two stories from my memory to write about, and here they are.

A Yi is an emerging Chinese writer with three books translated and published in English so far, including his latest work “Two Lives: Tales of Life, Love and Crime” and “A Perfect Crime,” which have gained recognition domestically and internationally. Growing up in a small town in Jiangxi province, A Yi worked briefly as a police officer in his hometown before becoming a sports editor. His literary journey began in 2008 with the publication of his short story collection titled “The Grey Story.” Since then, he has authored over a dozen novels and short story collections in Chinese. A recurring theme in A Yi’s work is the portrayal of lonely small-town life, exploring its darker aspects and delving into the minds of criminals, drawing inspiration from his experiences as a former police officer.

Dylan Levi King is a writer and translator. His most recent translations are Cai Chongda’s “Vessel” (HarperCollins) and Jia Pingwa’s “The Shaanxi Opera” (AmazonCrossing).

Author A Yi’s tale of bureaucracy and absurdity behind county officials’ futile attempt to put out a fire

China’s long quest to produce a great crime novel

Author Iron Head writes about the lives of youths who’ve grown up at the bottom of society

Timing Pully Is the latest card craze an unhealthy addiction for children or a lifeline for small-town shop owners?