NEW YORK — A deli in midtown is more than just a spot to grab a bite to eat. It is a place of prayer. Rather than selecting a bag of chips off the shelf, Muhammad Ahmed spreads out a small rug on the floor in the corner and offers worship.

For Ahmed, and thousands of Muslim ride-hailing service drivers like him, finding friendly establishments open to hosting daily prayers is a constant and necessary project in a city notoriously bereft of public bathrooms, parking spots and private spaces. Oilfield Camps

Like many devout Muslims, Ahmed prays five times a day at set times and, beforehand, performs a detailed act of ablution (cleansing) with clean water, known as “wudu.” For him and other Muslim Uber and Lyft drivers in the city, this daily prayer obligation and the associated rituals have a big impact on their driving.

“If I don’t find parking, then I don’t have any other option, so I skip one prayer and then for the next prayer, I offer both prayers at one time,” said Ahmed.

New York City, home to the iconic yellow taxicabs, has long relied on cars for hire, but the rapid growth of ride-booking companies — there are now nearly 80,000 ride-hail drivers compared to 13,587 taxis in the city — has exacerbated accommodation challenges.

The New York City Department of Transportation provides 38 relief stands in Manhattan, where drivers can park their cars for up to one hour. However, the stands often have only two to four parking spots each, and only 19 of the stands can legally be used by drivers for ride-hailing services.

And that has been true only since 2017, when the Independent Drivers Guild (IDG), a group that fights for drivers’ rights in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Illinois, advocated for FHV (for-hire-vehicle) stands in the city. Before that, only taxi drivers were allowed to use any of the relief stands.

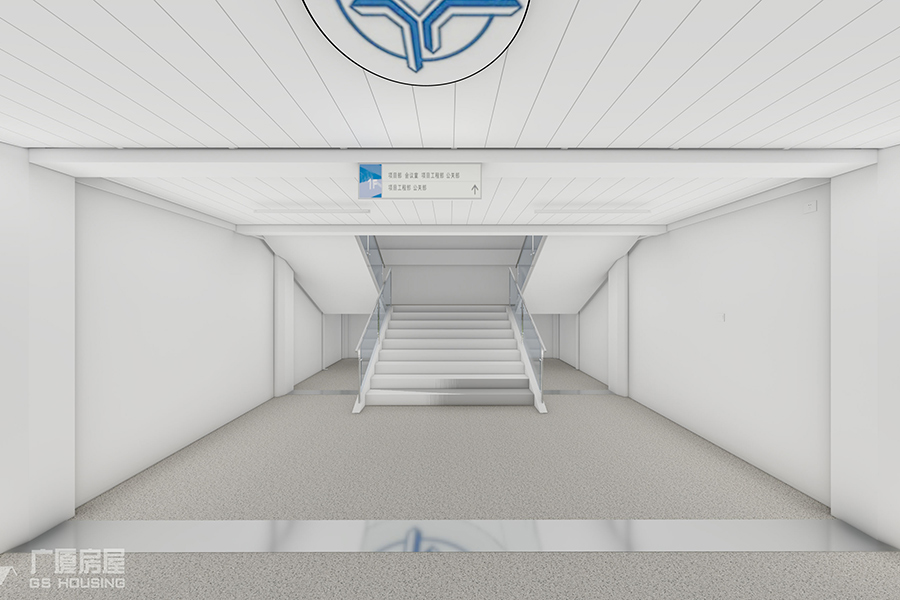

While the exact number of Muslims among the city’s ride-share drivers is unknown — about one-third of New York City’s yellow cabs are driven by Muslims — IDG knows many of its members are Muslim. Its office, located in Long Island City, has both a wudu station where drivers can perform their ablution and a dedicated prayer room with prayer rugs.

“We built the center with drivers in mind — to give them a nice rest area, a wudu area and a prayer room that they can access any time they want to. It is a step in the right direction, but it doesn’t solve the overall problem,” said Aziz Bah, organizing director of IDG New York and National.

Originally from Senegal, Bah, who is Muslim, began driving vehicles for ride-hailing in New York City in 2012 and knows the struggle of accommodating daily prayer while driving.

“When you get to the central business district in Manhattan, it gets super complicated to find a spot,” said Bah. “You just go in a circle until you miss your prayer time, or you might just risk parking somewhere really quickly to (go pray), and you come back and there is a $115 ticket waiting for you.”

If there is no mosque nearby, drivers like Ahmed, who makes his wudu and prays at the midtown deli, are forced to find other suitable spaces. This is particularly an issue at airports, where the drivers must be on standby in waiting areas, often located in garages and parking lots far from running water.

A group of Muslim drivers at Newark Airport improvised a water station to perform their wudu by attaching a tap to a rain barrel and filling it with bottled water. It sits on a small table next to a semi-permanent tent meant for prayer.

While this makeshift tap does the trick, it is still only a Band-Aid to a bigger issue, according to Sohail Rana, deputy director of IDG for New Jersey and Connecticut.

“Having a bathroom is not even a luxury … it is a necessity for people, and people who bring so much money to the city and pay taxes and fees deserve a proper system where they can park their vehicle and have a restroom available,” said Rana.

Arifa Tirmizi, an organizer at IDG, has been a ride-hail driver since 2016. She says IDG’s advocacy to secure more relief stands, bathrooms, and rest and prayer areas is vital for drivers’ wellbeing.

“Those things really help us because we can actually have peace of mind and know they’re located on a map. We can park over there and then we can run to the bathroom and make our wudu,” said Tirmizi.

According to Bah, IDG met with the New York City Department of Transportation last month to continue the conversation about fixing the lack of relief stands in Manhattan.

“One idea that I floated was for the DOT to develop something like a parking pass and to connect with the (ParkNYC) app,” said Bah.

The DOT also suggested a tentative plan to place more relief stands around city-owned parks, said Bah, so drivers could easily access public bathrooms inside the parks.

Ahmed would like to see the city take distance into consideration with regard to building out more relief stations.

“There should be at least one restroom within a square mile (of the relief stand) where we can go,” said Ahmed.

He would also like to see dedicated prayer spaces in the city.

For Tirmizi, the issue comes down to respect.

Steel Structure Construction “We need people to be considerate. Because we as Muslims are also part of this community, we are also people of color, we are also citizens of the United States, and, most importantly, we are also humans.” — Religion News Service