A 14-story residential complex in Valencia, Spain’s third-largest city, was devoured by a fire on Thursday, killing at least five people and injuring 15, by the latest count on Friday afternoon. The flames swept through the two contiguous buildings in just half an hour, raising questions about the way the complex was constructed.

Housing units inside the residential complex began to be marketed in 2006, and construction was completed in 2008, right in the middle of the property bubble in Spain. The complex is located in the northwest of Valencia, in the Nou Campanar neighborhood. Honeycomb Composite Panels

Like the entire real estate sector, the developer behind the building — a firm called Fbex — went into crisis. In 2010 it filed for bankruptcy after racking up €640 million ($693 million) in debt. The development, financed by Banesto — a bank that was later absorbed by Santander in 2012 — passed into the hands of the lender.

The complex had 138 “privileged homes,” with one, two and three bedrooms, according to Fbex’s promotional video, which also highlighted its “excellent construction materials and top quality finishes.” The complex was made up of two buildings, of 14 and 10 floors, which were joined by a panoramic elevator.

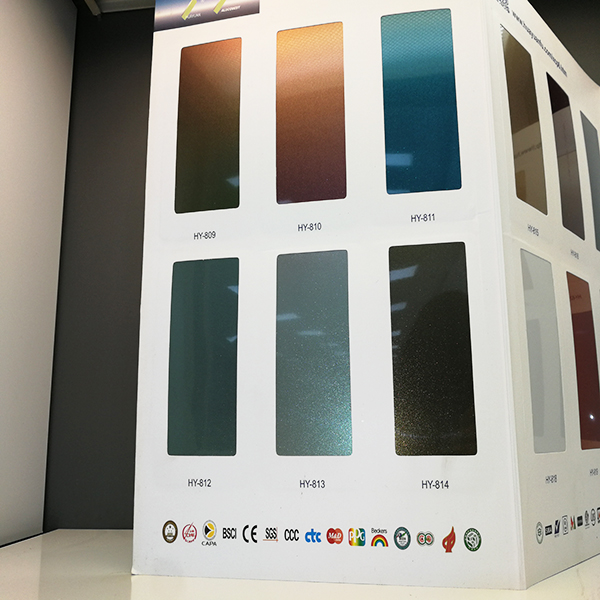

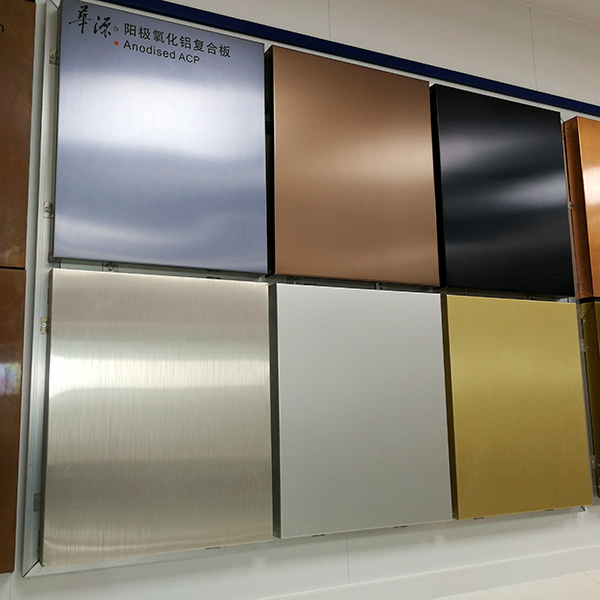

According to the video, the facade of the building was “cladded with an innovative aluminum material, ALUCOBOND.” In addition to the buildings that went up in flames in Nou Campanar, Fbex also built a complex known as the Navis Tower, with 20 floors and 162 homes, in the town of Mislata, less than two miles away. This building, like the ones devoured by the fire on Thursday, was cladded with ALUCOBOND, an aluminum composite that includes synthetic material.

This product is made up of a panel with two aluminum sheets and an insulating filler, which can be more or less flammable. As revealed on Thursday by Esther Puchades, the specialist who inspected the building a few years ago, the facade contained polyurethane as interior insulation, as well as the composite. On Friday, Puchades said that she does not know what material was used as insulation but that some of the facade materials had plastic components that quickly set alight.

However, José Manuel Fernández, the secretary of Spain’s Rigid Polyurethane Industry Association, said that this assessment is mistaken and that the building contained no polyurethane. “There is rock wool [or glass wool] in the air chambers, and the cladding is an aluminum composite with polyethylene. In other words, behind the aluminum sheets there is mineral wool, not polyurethane,” he insisted.

The Fbex promotional video states that the finishes and equipment in the buildings passed “rigorous quality controls during the building process.” “They forgot to say that each panel only had 0.5 mm of aluminum compared to 5 mm of solid polyethylene,” said David Calvo, an architect and former lawmaker for the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) in Valencia, in a message posted on X (formerly Twitter) on Thursday.

Calvo explained that these are the standard dimensions of the material, which have 10 times more filling than aluminum. It is a legal and regulated element “but, as was the case with uralite at the time, it is harmful,” added Calvo, who says that “hundreds” of buildings in Valencia were built in the same way. “It was a trend in the first decade of the 2000s,” he explained. “It was how buildings with a lot of surface area, a modern aesthetic and quick installation times were made.”

According to the architect, thousands of buildings throughout Spain have the same cladding, as its thermal properties make it good for insulating against both the cold and heat. “What’s more, it was unthinkable in those times to make a building with exposed brick, which was linked to a lower social status and to earlier times,” he said.

All rooms in the homes, except the bathrooms, faced outwards. This meant the flames, which spread over the building’s facade, directly affected bedrooms and lounge rooms, which contained many other flammable elements. According to the promotional video, the homes had a floating beech wood parquet floor, “a material that is still plastic,” said David Calvo. Furthermore, technical engineer and building installations expert David Higuera believes that the interiors must have also had other construction materials that helped the flames spread, adding that the damage to the ceilings can only be explained by the use of flammable insulation. The air conditioning, according to the promotional video, was through ducts, which did nothing to contain the blaze either.

The building had a ventilated facade ― with a chamber between the structure and the insulation ―, meaning firewalls were required between each floor, precisely to prevent, in the event of a fire, the flames from quickly spreading up or down the building. The building in Valencia contained these firewalls. However, at the time the building was constructed, the new building code ― which is more restrictive than the previous one regarding the use of materials ― had not yet come into effect. It was approved in 2006, but there was a transition period until it became mandatory. Furthermore, developers who had previously requested a license, as was the case with Fbex, were not subject to it.

Residential buildings do not require fire escapes: the building’s own staircase is the escape route. The current building code requires, however, that the walls of these stairways be made of materials with high fire resistance.

The buildings in Valencia passed an inspection when construction was completed in 2008, at which time an architect certified that the building met the requirements included in the construction license application. Due to its construction date, it did not require further inspections. In any case, as Calvo explains, the use of that material would have passed any control because it is legal.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Zinc Panel Subscribe and read without limits