This website uses cookies. to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking “Accept & Close”, you consent to our use of cookies. Read our Privacy Policy to learn more.

Lighting and Visualization Recommendations Address Ergonomics Led Surgical Lights Price

A Novel Approach to Solve Perennial Surgical Lighting Problems

Surgical Headlight Lighting Comfort is a Must for Surgeons - Sponsored Content

Is the Future of Surgical Lighting Automated?

The American College of Surgeons looks to prevent long-term injuries while ensuring safe and effective procedures.

T he American College of Surgeons (ACS) Division of Education Surgical Ergonomics Committee was created to address the ergonomic challenges surgeons often experience and to help improve their ergonomic well-being. Last year, the committee delivered the results of this initiative in the form of its Surgical Ergonomics Recommendations. Not surprisingly, surgical lighting and visualization was an included subject of focus.

A major issue surgeons often face in ORs is improper lighting and display orientation. This can not only adversely affect performance, but also cause eye strain and musculoskeletal fatigue that could lead to limitation of practice, long-term disability and the need for corrective surgery. To combat these concerns and protect the health of surgeons while ensuring safe and effective surgery, the ACS committee delivered these recommendations surrounding surgical lighting and monitor placement:

During open surgery: Ensure that the open surgical field has high illuminance using two or more OR lights at different angles. Avoid creating shadows from a single light source caused by a surgical team member’s head. ACS recommends placing the overhead lights between the surgeon and assistant in most cases.

During laparoscopic surgery: Room lights should be dimmed to reduce glare and contrast on display monitors while still offering enough ambient light that the surgical team can move safely throughout the room. Any display monitor used during a laparoscopic surgery should be placed directly in front of the surgeon with its upper boundary at eye level and the center of its screen slightly below eye level in order to facilitate and maintain a neutral neck posture.

During robotic surgery: ACS recommends adjusting viewer height so the user’s back is not crouched, and adjusting viewer tilt to minimize forward flexion. The surgeon should avoid pushing their forehead excessively into the console’s headrest when focusing on a case, and take advantage of 3D visualization when available to improve depth perception.

ACS recommends that teams preplan lighting and monitor positioning before and between every case with these recommendations in mind.

To prevent injury over the long term, ACS also advises surgeons to take a few minutes throughout the day to stretch their neck and shoulders, as well as to consider transitioning, when appropriate, from performing open surgeries to robotic-assisted procedures to take advantage of their improved ergonomics.

At a surgeon’s request, engineering students develop an automated system that reduces shadows and alleviates ergonomic issues.

M unish Gupta, MD, was confident that the length of some surgeries could be reduced by up to 25% if OR teams didn’t need to spend so much time manually adjusting boom-mounted surgical lights throughout procedures.

With that in mind, the orthopedic spine surgeon at Washington University in St. Louis asked a team of engineering students from Rice University in Houston if they could build an automated and tunable operating room lighting system, according to an article in university publication Rice News.

The students did just that, creating a touchscreen-based system that eliminated not just the need to manually adjust overhead surgical lights but also the need to wear headlamps, which can be an ergonomics challenge for many surgeons who find they must keep their heads perfectly still as they work, leading to neck strain.

The system features four separate light clusters mounted on an overhead frame. Each cluster is mounted onto a 3D-printed circular base that can adjust its position and the angle of the lightbulbs, so the beams of light can be turned and pointed wherever needed.

The enterprising students also mounted a lightweight camera on the frame to support an app they are developing that will provide a video feed of the operating table. Using the app, a surgeon would be able to click on and drag a circle on top of the video feed to select a specific area on which the lights should focus. Because the lights are coming from different directions, a stadium lighting effect is created that reduces shadows.

“We’re trying to create a system where surgeons can press buttons on a touchscreen, and it’ll point lights at a target area in the operating room,” says team member and engineering student Justin Guilak. He notes it can be difficult for surgeons or perioperative staff to make manual adjustments that light up an exact spot at the proper intensity. He says the system also alleviates the shadowing that can occur when multiple providers are wearing headlamps in the sterile field.

The innovative project, featured at an annual engineering showcase and competition in April in Houston, exemplifies that surgical lighting, like everything else in surgery, is never a finished product but rather can and should be improved and enhanced over time. Check out this video of the students’ impressive ideation and execution of their novel lighting system.

Selecting the right lighting for versatility, function, performance and brightness makes all the difference in a surgical procedure.

W ith patient safety always in mind, OR leaders are careful to select top quality surgical lights for their surgeons and perioperative teams to provide optimal visualization during surgical procedures. For years, choosing surgical lighting has been a challenge. The right lighting is critical not only for optimum patient safety but for staff comfort and safety as well.

In fact, poor lighting is a safety hazard that can lead to injuries, and it can also affect the quality and precision of the surgery itself. Surgical lighting is complex, sophisticated, and is often customized for an OR. For that reason, the purchase of this equipment is a multi-step process to ensure that the right equipment is acquired to perform successful and safe procedures.

New standards in surgical lighting can help organizations meet this goal and avoid pitfalls. For example, using LED systems that emit pure white light will allow surgeons to assess and interpret the anatomical appearance of the surgical cavity accurately and consistently. A uniformed beam eliminates hot and cold spots and reduces eye fatigue.

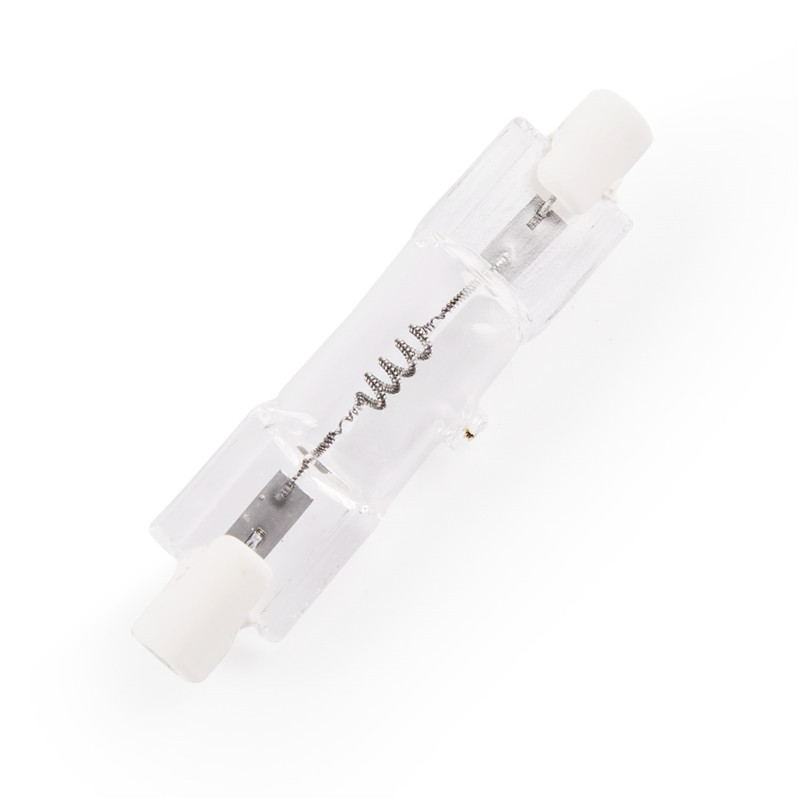

There are various types of surgical lights, and each type plays a specific role in illumination before, during and after a medical procedure. They can be categorized by lamp type or mounting configuration. Two lamp types are conventional (incandescent) and LED (light emitting diode). LEDs can be extremely small, durable, reliable and have a much higher bulb-life rate than conventional lighting.

Quality lighting is vital for every OR. Three of the most common methods include overhead/operating lights, headlights/illuminated loupes and in-cavity lighting. Overhead lights are typically LED or incandescent and can be mounted on a ceiling or wall. Headlights are wearable technology that provide brightness, dependability and small spot size by enabling light to follow the attention of the surgeon and enhance mobility and shadow-free illumination. These headpieces can be battery-powered or connected to a standalone light source with a fiber optic cable.

One of the challenges of headlamps is that they can be uncomfortable to wear and can result in head and neck pain after an extended period. When connected to fiber optic cables, movement can be limited, requiring the surgeon to detach the cord for the light source and then reattach it as they move around during the procedure. Battery-powered headlights are another option, but they come with problems. Most still use a cord going from the headlight to a battery pack clipped to the waist of the user, which can cause pressure and neck pain.

New technology, however, allows for a truly cordless headlight. Headlights with very lightweight batteries that are balanced on the user’s head are the best option. Designed with the user in mind, these provide comfort bands that do not squeeze the user’s head.

Headlights are a necessary adjunct for deep, lateral, or narrow surgical sites. Many surgeons report using them the majority of the time and some even 100% of the time.

The MedLED Spectra® eliminates trade-offs between different types of lighting technology and sets a new standard with its advanced features. The MedLED Spectra® is a versatile LED surgical headlight, it is a cordless headlight that delivers optimum lighting, long-lasting battery life and maximum wearing comfort – offering surgeons a better experience to confidently provide patient care. With advanced features like a patented padding system, the Spectra Headlight delivers the comfort needed to forget it’s even there. Adjustable, advanced beam technology offers the light intensity to illuminate deep cavities.

The MedLED Spectra® Surgical Headlight is a lightweight, portable source of bright, unobstructed light for surgeons. It features Dual Everlast™ batteries that are integrated into the headband and can be changed without losing power. Its advanced beam technology provides an optimal amount of light during dental, clinical, or surgical procedures. The headlight comes in three light options (100k, 200k, or 300k LUX) and two configurations of headlight accessories: 1) A standard kit consisting of a headlight, two batteries, wall plug/USB and convertible top; and 2) A hospital kit consisting of a headlight, six batteries, four-bay battery charger, wall plug/USB and convertible top.

Surgical lighting is one of the most critical factors in the OR environment. The primary function of surgical lighting is to illuminate the operative site on and/or within a patient for ideal visualization by OR staff during a surgical procedure. Without the correct light source, the surgeons’ risk of making mistakes increases and could affect surgery outcomes and lead to increased malpractices claims.

Note: MedLED® is a registered trademark and product of Riverpoint Medical and is distributed in the USA and Canada by STERIS. For more information go to: https://www.steris.com/healthcare/products/surgical-lights-and-examination-lights/medled-spectra-surgical-headlight?utm_source=Digital+Ad&utm_medium=Ad&utm_campaign=MedLED+Spectra+&utm_id=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.steris.com%2Fhealthcare%2Fproducts%2Fsteris-smoke-evacuation-system

Researchers predict technology will facilitate more appropriate, precise and safe illumination in the OR.

A research team from Queen Mary University of London that recently examined the limitations of current surgical lighting methods poses the question: Is automated surgical lighting the potential solution to those limitations?

The team’s paper, published this summer in the journal The Surgeon, posits that the current state of surgical lighting needs improvement, and that automated lighting could hold the key.

The researchers define automated lighting as a system “that could be automatically operated by the surgeon or team, allowing for greater sterility and swifter transitions of light repositioning.” They say automated lighting systems integrated into ORs could tackle recurring and frustrating issues with ergonomics and manual readjustments by employing technologies such as thermal imaging, artificial intelligence (AI) and 3D sensor tracking algorithms.

The paper first examines the uses, advantages and disadvantages of today’s four main forms of surgical lighting: surgical lighting systems, headlights, lighted retractors and operating microscopes.

“Today, surgical lighting typically consists of a large central light source with secondary, accompanying sources of light that can be positioned manually to increase illumination to the surgical site,” the paper states. “There has also been increased understanding that simply increasing the brightness of surgical lighting does not necessarily result in better quality lighting, as excessive intensity of a light source can create glare, which decreases contrast between anatomical structures.”

Other issues that need to be considered with current surgical lighting methods include provider safety (particularly eye strain), efficiency, sterility, decontamination and cost, the paper states. It then identifies potential improvements that automated lighting systems could bring, including reductions in manual adjustment “interactions” that don’t just consume time but also can distract staff, result in mechanical problems and collisions of light sources or cause surgical site infections.

”There are some evident safety and economic downsides to all the current forms of surgical lighting and, as clinicians, we must optimize our time in the OR and keep our patients and ourselves safe,” the paper states.

The researchers say automated lighting systems show the potential to leverage AI by “learning” to vary lighting depending on the nature of the tissue being tracked. AI could also “learn” an individual surgeon’s optimal light preferences depending on which features of tissue are involved. They say 3D tracking systems can assist surgeons with physical assessment — especially in areas such as kinematics, skeleton pose tracking and marker tracking — while thermal imaging could help surgeons differentiate between areas of the surgical site based on the amount of thermal radiation being emitted, and automatically readjust the camera based on that information.

However, the researchers admit that more focused studies and development must occur before automated lighting systems are optimized enough that they can be safely and successfully integrated into ORs.

“In particular, further efforts should be made to model the use of these approaches in an experimental setup to best represent their workings in an OR,” they write. They conclude, however, that automated systems are unquestionably the future of surgical lighting.

Duke Health strategizes to prevent bad fits that lead to injury.

D uke Health recently rolled out a program designed to prevent surgeon injuries by addressing ergonomic risk factors that may lead to musculoskeletal disorders. Based on observational study and monitoring of surgeons at work, a significant element of the program zeroed in on the fit of the loupes surgeons wear to magnify visualization of tissue and pinpoint instrument placement.

Poorly fitted loupes can cause surgeons to bend their necks at awkward, uncomfortable angles during surgeries, which often leads to strain-related injuries. To remedy this common issue, Duke Health made some major changes to its loupe-fitting practices with the aim of helping the next generation of surgeons avoid injuries that more experienced surgeons have developed over time.

To ensure interns are better educated on the proper way to wear loupes, residents consult with them prior to their fittings. “The residents guide the interns on what to look for in a fitting and how the loupes should fit,” says Marissa Pentico, MS, OT/L, CPE, ergonomics coordinator at Duke Health. “That’s been really helpful because interns have been basing their decisions solely on what the vendors told them.”

Interns are also afforded the ability to make modifications if they’re experiencing problems with their loupes. “Within three months, the expectation is that interns will have a follow-up session with the vendor if they need to change the fit,” says Ms. Pentico. “Vendors know they must be available to make the changes within that time frame.”

An interesting additional component of the program is the location of the fittings. Duke Health moved them to a SIM lab with a height adjustable table, a training mannequin and suturing kits. The change, says Ms. Pentico, ensures interns are being fitted while they’re performing a suturing task at a table height that they indicate is in line with what they typically use in the OR.

Ms. Pentico says Duke Health’s emphasis on proper fitting of loupes is crucial because of how long many physicians will spend using this important visualization equipment. “We have attendings who have been wearing the same loupes for 15 to 16 years, so we need to get our interns started off right,” she says. OSM

A generational gap has formed in the workplace and beyond between the twentysomethings of Gen Z and seemingly everyone else....

The date was set for Knee Replacement No. 1, aka “Laverne....”

In March, the Outpatient Surgery Magazine editors headed down to Nashville to attend AORN Global Surgical Conference & Expo, the 71st edition of the popular event....

Operation Theatre Light Connect with 100,000+ outpatient OR leaders through print and digital advertising, custom programs, e-newsletters, event sponsorship, and more!