You’ve heard the statistics: A crawler undercarriage typically accounts for 20 percent of a dozer’s purchase price, but 50 percent or more of its lifetime repair tab. With that potential repair expense at stake, doing what you can to trim undercarriage expenses can considerably lower per-hour operating costs. That, in essence, is “undercarriage management”—a discipline (part science, part intuition, all refined by experience) that encompasses machine operation, routine maintenance, periodic evaluation, and, toughest of all, judgment calls about how best to handle wearing components.

Ignoring bulldozer undercarriage management can be costly: “Wait until something catastrophic happens, like breaking a chain on the job site, then it’s field service, and you’re out there lifting and shoring to get the tractor out of the mud,” says Steve Deller, product support manager for West Side Tractor Sales, an equipment dealer in suburban Chicago. “Had the owner in that situation been just a little proactive—measuring wear periodically and following a few basic recommendations—that expense might have been avoided.” Itr Bucket Teeth

A number of equipment manufacturers have developed premium undercarriage systems to address a primary source of undercarriage wear, namely, external wear on the bushing.

The John Deere SC-2 design, for example, fuses super-hard metallic slurry to the outside of the bushing. The coating, says the company, can provide double the life of conventional bushings before requiring a turn—or might eliminate the need for turning in some applications. Case also says that its CELT (Case Extended Life Track) system can double conventional bushing life. This system places a hardened bushing over the standard bushing, allowing the larger outer bushing to rotate and, thus, eliminate scrubbing between the bushing and sprocket.

Caterpillar’s SystemOne uses long-life components throughout the undercarriage, and a focal point of the design is a rotating bushing that uses double seals at the bushing/link interface. Komatsu’s PLUS design, (Parallel Link Undercarriage System), which also uses a rotating bushing and dual seals, incorporates an additional bushing segment between the seals on each side of the chain.

The consensus, generally, is that the most value is achieved from premium undercarriages when tractors work frequently in particularly abrasive materials. Brad Davis, a consultant with Quick Trax of Texas, suggests, however, that machine owners considering premium undercarriages assess the price/value relationship before making the investment. The company’s shop routinely works on all types of undercarriages, he says, and “from what we’ve seen, the standard undercarriage generally is the most reliable and also the most cost- efficient in terms of life expectancy and replacement costs.”

“Proactive” management begins with good operating and maintenance practices, says Bruce Boebel, Komatsu America’s crawler dozer product manager. The former, he says, includes avoiding—as much as practical—high ground speeds, excessive reverse operation, track spinning, counter-rotation, and same-direction turning on large jobs. Good maintenance, says Boebel, ranges from daily shoveling out the tracks and frequently checking track tension, to periodically measuring wear and making informed decisions based on the results.

Boebel reminds equipment managers, also, that machine features can assist with undercarriage management. For example, the transmission controller in some machines can be programmed to limit reverse speeds; undercarriage wear is at its worst when the machine reverses, and excessive speed accelerates the process.

Telematics systems can be helpful, as well, says Boebel. Because these systems report working time versus idle time, periodic undercarriage measurement can be scheduled based on actual working hours (not hour-meter readings). And if the system also reports forward-travel time versus reverse-travel time, and if reverse operation seems excessive, then perhaps the operation needs revamping to ease stress on the undercarriage, or maybe operators need more training.

Most crawler dozers leave the factory with SALT (sealed and lubricated track) chains, which use pins having an internal reservoir of oil that flows through a radial hole in the pin and into the annular space between the pin and bushing. Seals in the link counterbores (into which the bushing ends seat) retain the oil. As long as seals remain effective, the oil retards internal wear between the pin and bushing as the pin rotates within the bushing during normal operation.

(Some premium-undercarriage designs, Caterpillar’s SystemOne and Komatsu’s PLUS, for example, use bushings that do not seat in the link counterbores in a conventional manner.)

Most hydraulic excavators come from the factory with “greased” chains, which are assembled with heavy grease between the pin and bushing. According to Brad Davis, a consultant with Quick Trax of Texas, a company that sells and services undercarriage components, the greased-track’s seals usually aren’t as effective as those in SALT chains and eventually leak, allowing wear between the pin and bushing.

Tim Nenne, an undercarriage market professional for Caterpillar, concurs: “The grease does not stay in place for an extended period of time, like the oil in a SALT chain. After about 2,500 hours of operation on small and medium excavators, internal wear usually begins. Caterpillar does, however, use a SALT seal on its large excavators, which allows these machines to run longer without internal wear.”

When pins and bushings wear internally due to lack of lubrication, wear occurs primarily on one side of the pin and on the mating surface of the bushing’s inner diameter. Wear changes the geometry of the track by allowing track pitch (the distance between pin centers) to extend, resulting in a “stretched” chain that runs loose.

Normal wear on the outside of the bushing also occurs primarily on one side, the reverse-drive side, because the bushing rotates under considerable load at the top of the sprocket when the machine reverses. Although the bushing rotates at the same spot during forward travel, the load in minimal.

This primarily one-sided wear of pins and bushings allows these parts to be “turned”—bushings rotated 180 degrees and pins flipped end-for-end—to bring new surfaces to working areas, both internally and externally. Turning restores track pitch and can prolong undercarriage life by enabling the chain to last until links and rollers need attention.

“Turns” on today’s machines with lubricated tracks can be either “wet” or “greased.” During a wet turn, the pins are refilled with oil, a process that involves pulling a vacuum in the pin’s oil reservoir (through a self-sealing plug in the end of the pin) and drawing in new oil. If the assembly won’t pull a vacuum, chances are that the seals will leak. With a grease turn, pins and bushings are simply reassembled with heavy grease.

Although turning pins and bushings has been somewhat of a maintenance staple in the past, the economic value of the practice is getting a harder look today.

Theoretically, says Quick Trax’s Davis, pins and bushings in a SALT chain should need turning only because of external wear on bushings, since the assembly’s oil supply works to minimize internal wear. And with some machines and in some applications, that’s true.

But according to Dawn Barefoot-Lynch, a customer service advisor specializing in undercarriage for West Side Tractor Sales (which has 10 locations in northern Illinois, southern Michigan and throughout Indiana), her experience is that internal wear generally exceeds external wear on a SALT chain.

“It’s just a matter of time before a SALT joint goes dry,” says Barefoot-Lynch. “Controlling factors include ground conditions and track width—many dozers are LGP [low ground pressure] and wider pads place more side torque on seals, bushing ends and link counterbores.

“You might see tracks that initially look like good candidates for a turn, with bushing wear at less than 50 percent. But when you measure the undercarriage, there’s 40 percent stretch. Chances are that when you get the tracks on the press, there will be so many dry joints that a wet turn isn’t feasible—the sealing surfaces are compromised, probably enough that the joints won’t hold oil for as long as we’d like, even with new seals and thrust washers.

“We see a shift away from wet turns,” says Barefoot-Lynch. “The labor has become expensive and, at least in this area, it’s not the externals that are compromised in most situations, it’s the internals. It’s always a judgment call, but in some instances, it makes sense to let the chain run out to get maybe another 500 to 700 hours, then, if link height and counterbore condition are good, you can install pin-and-bushing kits—or, depending on the size of the tractor, just install new chains. On small machines, you might find only a $500 difference between doing a turn and new chains.” (Kits include pin, bushing, seals, thrust washers and pin plug.)

According to Quick Trax’s Davis, most bushings have grooves formed from the old seals, and once turned, bushings might not mate properly with new seals. In his opinion, this accounts for the growing popularity of grease turns, using the old seals to save costs.

“In our shop, the cost difference between the two [wet turn versus grease turn] is usually 30 to 40 percent, depending on the particular machine and parts availability,” says Davis. “We typically see no more than a 20-percent difference in life between the two.”

Caterpillar’s Nenne agrees that the increasing cost of labor for bushing turns has made the practice less economical, especially for small- and medium-size tractors. He points out, however, “if a large track-type tractor needs a bushing turn to maximize the life of the link/roller system, there is still value in doing so—even at today’s labor costs.” He says, too, that advances in bushing and sprocket metallurgy have extended the life of these components in some instances “to a point that many owners no longer need to do a turn to get the most out of a link/roller system.”

Nenne reminds fleet managers, also, that some manufacturers offer what the industry usually calls “wet-turn assurance.” Caterpillar, for example, he says, guarantees that SALT bushings can be turned wet, and if the seal groove on the end of the bushing is deemed unsuitable, the company will replace those bushings to guarantee a quality wet turn. Barefoot-Lynch adds that these guarantees can have time or hours-of-use limits, which might be cut in half for tractors with wide shoes.

Making decisions about how best to handle a wearing chain, says Deller, obviously involves a number of factors—including the size of the tractor, its age, current condition, application, cost of components, and how the owner anticipates using the machine going forward.

“Look at all the options—wet turn, grease turn, pin-and-bushing kits—or maybe the best value is in running the chains for the hours left in them, then installing new chains. You might find that the cost of doing a turn is a significant percent of the cost of new chains.”

“Everybody used to expect the excavator undercarriage to last forever, because they don’t travel much,” says Deller. “But with today’s larger buckets, every time an excavator swings over the side it pivots on the track chain and wears the internals. The wider the shoe, the more stress on the links and bushings.”

Stan Taylor, also a Caterpillar undercarriage market professional, makes the further observation that hydraulic excavators often are tracked incorrectly—with the sprocket in the front—a practice that tightens the track, increases internal stresses, and causes accelerated wear.

Says Barefoot-Lynch: “At least in this area, external wear on an excavator is minimal, but the chains get so extended, that when you take them apart, the counterbores are ‘egged’ [severely worn out-of-round], and if you try to push back a new pin and bushing, they’re not going to be true. Some customers actually remove a link to shorten the track in order to keep it in reasonable tension—it’s a patch, but it works. I never recommend doing anything with an excavator chain; just run them out and replace them.”

Caterpillar’s Nenne concedes that fewer owners attempt to manage an excavator undercarriage than do those with dozers, but says “a properly managed [excavator] undercarriage may get additional value by doing a pin-and-bushing turn.”

“In many cases,” says Nenne, “excavator shoes, rollers and idlers can be reused for a second link assembly, but when the undercarriage is not being properly managed, it will lead to unnecessary replacement of components and added cost.”

Obviously, undercarriage management is not a black-and-white issue; conditions and situations vary with every machine, as do opinions about the best way to keep machines moving at the lowest cost. But on some issues, universal consensus has been reached.

First, as Komatsu’s Boebel has noted, exercising reasonable care when operating crawler machines, especially dozers, can make a notable difference in undercarriage life—as can practicing good routine maintenance.

“My experience is that customers who regularly clean out the tracks and make sure that track tension is adjusted properly definitely get extended service from the undercarriage,” says Barefoot-Lynch. “Some will argue that it’s not effective, but it is.”

Another point of consensus is the importance of having the undercarriage measured and evaluated at regular intervals by an experienced dealer undercarriage expert—the more experience the better. How often? General agreement is between 800 and 1,000 hours.

“We have one large-fleet manager who measures every 500 hours,” says Deller, “because he’s trying to trend wear characteristics, looking for that sweet spot that will give optimum return on undercarriage investment. But, normally, 1,000 hours is good.”

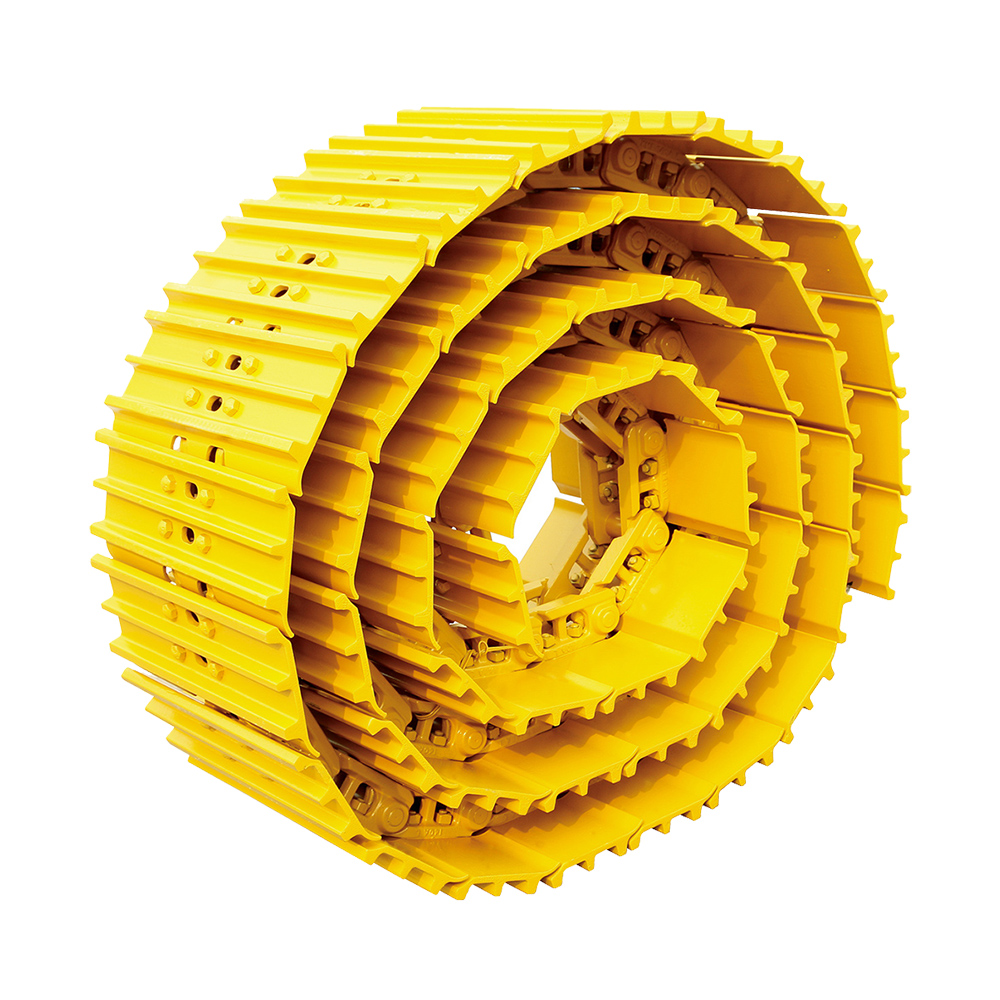

Undercarriage Spare Part Perhaps most important in managing an undercarriage, says Barefoot-Lynch, is to keep an open mind toward different recommendations and to the range of OEM and aftermarket undercarriage products available—it’s possible to mix quality components from both sources with money-saving results, she says. Don’t get stuck in the “that’s-the-way-we’ve-always-done-it” rut, she advises, because the old way might not be the smartest way anymore.